Education

Privilege, agency, and the climate scientist’s role in the global warming debate

Background

One of the biggest surprises I found upon my return to the University of Victoria after spending 7 1/2 years in the BC Legislature was the overall increase in underlying climate anxiety being experienced by students in my classes. I’ve been teaching at the university level since the mid 1980s and for most of this time, the students in my classes considered global warming to be an esoteric and highly uncertain future threat. While some would express concerns about the growing concentrations of atmospheric greenhouse gases, very few understood, or even cared, how climate change could hypothetically affect them. It was always a problem that others, somewhere else in the world, might have to deal with sometime down the road – but not any more. My experience with this new generation of undergraduates is that they are both very aware of, and deeply troubled by, the threat of global warming. I am beginning to detect a sense of hopelessness and despair within growing numbers of youth. And this troubles me immensely.

For many years I, and my climate science colleagues around the world, spoke truth to power as we continually raised concerns about the ongoing consequences of dumping millions of tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere every year. But our warnings fell on deaf ears, or at least ears damaged by the never ending stream of spin, obfuscation and rhetoric being offered up by lobbyists, vested interests, charlatans and others desperate to maintain the fossil-fuel status quo. Yet those days are gone. So much has changed.

Perhaps the most notable increase in public awareness can be attributed to Greta Thunberg and her Skolstrejk för klimatet (School strike for climate). Starting from her lone Friday demonstrations on the steps of the Swedish parliament in August 2018, her movement quickly gained international attention leading to locally-organized Fridays for Future demonstrations around the world (see Figure 1 for images from a Friday, September 19, 2019 demonstration on the lawn of the BC Legislature).

Figure 1 : Four images taken on Friday, September 20, 2019 at a Global Week for Future demonstration on the lawn of the BC Legislature.

At the same time, extreme weather and climate extremes are seemingly becoming the norm rather than the anomaly, with hardly a day going by without a weather disaster somewhere in the world headlining the nightly news. And while in the past, these extreme weather events may have seemed to be someone else’s problem living elsewhere in the world, today no one is immune. Even meteorological terms like “heat domes”, “atmospheric rivers” or the “polar vortex” are becoming commonly used in casual conversation.

The cumulative efforts of so many over so many years in pointing out the importance of curtailing greenhouse gas emissions is finally paying off. Public awareness and desire for action is no longer a barrier to advancing climate policy. For example, one Pew Centre global survey spanning 17 countries in Europe, the Asia-Pacific, and North America indicated that 80% of people surveyed were “willing to make [a lot of or some] changes about how [they] live and work to help reduce the effects of global climate change” (Bell et al., 2021). The greatest barrier, in my view, remains political will. Too many of our elected representatives end up treating politics as a lifelong career instead of a sense of civic duty wherein you step in for a few years, do your part, then step out and let others take over. After a while, one might cynically expect such career politicians to naturally start focusing more on populist and short term policy measures that can successfully be developed and implemented prior to the next election. It would allow that politician to identify short term successes as direct evidence that they were delivering results for their constituents.

By its very nature, climate policy requires a much longer term perspective to be taken. It requires recognition that today’s decision-makers wont have to live the consequences of the climate-related decisions (or lack thereof) that they make. Yet I have always believed that global warming represents the greatest opportunity for innovation, creativity and economic prosperity the world has ever seen since every environmental challenge can also be viewed as an opportunity for innovation and creativity as we seek to address the underlying challenge. Instead of dwelling on the scale of the challenge and hence its apparent hopelessness, which only feeds an individual’s climate anxiety, it can be incredibly empowering to pivot to a focus on developing climate solutions. And herein lies an opportunity for the climate science community.

Climate Anxiety

Climate anxiety is a very real psychological and emotional response to concern about uncertain future climate change impacts (American Psychological Association, 2017, Doherty and Clayton, 2011). Defined as a chronic fear of climate or environmental doom, an individual’s chronic climate anxiety is magnified by extreme weather and climate events that have been experienced personally and/or by those in their close networks.

For example, climate anxiety in North America increased in the summer of 2021 because of intense, record-breaking heatwaves and wildfires (Bratu et al., 2022). As well, increased climate anxiety was almost certainly triggered in those who experienced September 2022’s widespread destruction caused by Hurricane Fiona and Ian’s historic winds, wave activity and storm surge.

Figure 2: Canadian Space Agency satellite images taken on August 21, 2022 (left) and September 25, 2022 (right). Extensive coastal erosion of Prince Edward Island was caused by historic storm surge and wave activity associated with Hurricane Fiona.

Figure 2: Canadian Space Agency satellite images taken on August 21, 2022 (left) and September 25, 2022 (right). Extensive coastal erosion of Prince Edward Island was caused by historic storm surge and wave activity associated with Hurricane Fiona.

Climate scientists are not immune to climate anxiety. Many within our community have felt compelled to speak out publicly regarding the causes, consequences, and seriousness of global warming. Others have signed petitions, penned letters, written books and commented on social media sites. However, few have actively sought election to government office. This is unfortunate as I continue to believe that political will remains the greatest barrier to advancing climate policy including the decarbonization of global energy systems. But instead of helping to generate that political will, a large cohort of the climate science community, in an attempt to deal with their own climate grief, has heightened rather than alleviated climate anxiety in civil society.

Through this article, I hope to encourage that community to reflect upon the privilege and agency they have to refocus and mobilize their efforts towards advancing climate solutions within society, and to appeal to their sense of civic duty to inspire more to seek elected office. In particular, I argue that:

- Inaccurate scientific messaging associated with the 2018 IPCC Global Warming of 1.5°C report is feeding climate anxiety, and this is leading to despair in youth.

- There are more effective ways for scientists, armed with privilege and agency, to advocate for climate policy than fear-based messaging and civil disobedience.

As Albert Einstein famously noted: “Those who have the privilege to know have the duty to act, and in that action are the seeds of new knowledge.” After reading the rest of this blog, I hope you agree that this quote could be expanded with an additional sentence. “And as the new knowledge grows, the solutions to global warming are revealed.”

Scientific messaging is feeding climate anxiety

The 2018 IPCC Special Report outlining greenhouse gas emission pathways to limit warming to 1.5°C above preindustrial levels (IPCC, 2018) almost certainly contributed to an escalation of overall climate anxiety in recent years. The Special Report was a response to an invitation from signatories to the UNFCC as part of the Paris Agreement. The 2015 Paris Agreement, joined by 193 member states, has the specific goal of:

Holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change (UNFCC 2015).

The aspirational 1.5°C target was added in response to lobbying by small island states (and their allies).

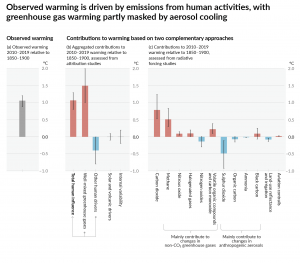

While the scientific community responded by outlining pathways to mitigate warming to 1.5°C in (IPCC, 2018), the subtleties embedded within the report seem to have been lost in its dissemination to the public. It is well known that the world has already warmed by 1.2°C since preindustrial times, and if we immediately eliminated all fossil fuel combustion worldwide, we would warm by an additional 0.5°C (IPCC 2021; see Figure 2) as the direct and indirect cooling global effects of aerosols (also associated with fossil fuel combustion) dissipate through gravitational settling and precipitation scavenging. The Earth would warm further as we equilibrate to the present 508 PPM CO2e (NOAA 2022) greenhouse gas loading in the atmosphere, and that is not counting the permafrost carbon feedback which could add another 0.1° to 0.2°C this century to committed warming (Macdougall et al, 2013).

In other words, meeting the 1.5°C target requires an immediate global scale up of negative emissions using technologies that have yet to be developed. Given socioeconomic inertia in our built environment (Matthews and Weaver, 2010), the scale of negative emissions required, and the preponderance of more urgent political priorities (i.e. healthcare, housing, inflation, the economy, the war in Ukraine and so forth), it is not possible for the world to meet the 1.5°C target.

Figure 3: Observed global warming (2010-2019 relative to 1850-1900) and the contribution to this net warming by observed changes to natural and anthropogenic radiative forcing. Reproduced from IPCC (2021).

Climate anxiety is also fueled by media messaging related to the perception of a looming climate ‘crisis’ (Crandon et al., 2022). Take the anxiety effect of popular messaging related to the aspirational goal of remaining below a 1.5°C global warming threshold (IPCC, 2018). “We have only 12 years left to limit climate change catastrophe, warns UN” was the headline of a story published in the Guardian on October 8, 2018; “Only 11 years left to prevent irreversible damage from climate change, speakers warn during general assembly high-level meeting” was the headline of a press release issued by the United Nations on March 28, 2019 during its 73rd session (UN, 2019); “Climate change: 12 years to save the planet? Make that 18 months” was the headline of a BBC News story on July 24, 2019 (BBC, 2019).

Climate anxiety is also fueled by media messaging related to the perception of a looming climate ‘crisis’ (Crandon et al., 2022). Take the anxiety effect of popular messaging related to the aspirational goal of remaining below a 1.5°C global warming threshold (IPCC, 2018). “We have only 12 years left to limit climate change catastrophe, warns UN” was the headline of a story published in the Guardian on October 8, 2018; “Only 11 years left to prevent irreversible damage from climate change, speakers warn during general assembly high-level meeting” was the headline of a press release issued by the United Nations on March 28, 2019 during its 73rd session (UN, 2019); “Climate change: 12 years to save the planet? Make that 18 months” was the headline of a BBC News story on July 24, 2019 (BBC, 2019).

To amplify the urgency of further climate action, “Climate Clocks” were developed that purported to count down days until it was too late to avoid the worst impacts of global warming (see here and here). It is unclear how watching a countdown to catastrophe would do anything other than increase climate anxiety and instill a sense of hopelessness and despair. Political rhetoric from those with large followings, such as when Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez proclaimed “The world is going to end in 12 years if we don’t address climate change” (USA Today, 2019), also contributes to increasing climate anxiety.

To amplify the urgency of further climate action, “Climate Clocks” were developed that purported to count down days until it was too late to avoid the worst impacts of global warming (see here and here). It is unclear how watching a countdown to catastrophe would do anything other than increase climate anxiety and instill a sense of hopelessness and despair. Political rhetoric from those with large followings, such as when Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez proclaimed “The world is going to end in 12 years if we don’t address climate change” (USA Today, 2019), also contributes to increasing climate anxiety.

![]() Inherent in the 12 years left narrative, and the IPCC 1.5°C report is the implied notion that there is something magical about the number 1.5°C. Of course, there is no scientific rationale to justify an acceptable warming threshold of 1.5°C instead of 1.3°C or 1.672°C. Any defined level of ‘acceptable’ warming obviously involves an assessment of societal values and those will clearly be different depending on where you live in the world.

Inherent in the 12 years left narrative, and the IPCC 1.5°C report is the implied notion that there is something magical about the number 1.5°C. Of course, there is no scientific rationale to justify an acceptable warming threshold of 1.5°C instead of 1.3°C or 1.672°C. Any defined level of ‘acceptable’ warming obviously involves an assessment of societal values and those will clearly be different depending on where you live in the world.

In fact, even the 2°C threshold for acceptable warming originally only entered the public arena shortly after the IPCC released its Second Assessment Report and prior to the establishment of the Kyoto Protocol. In 1996, the Council of the European Union concluded:

The Council recognizes that, according to the IPCC S.A.R., stabilization of atmospheric concentrations of CO2 at twice the pre-industrial level, i.e. 550 ppm, will eventually require global emissions to be less than 50% of current levels of emissions; such a concentration level is likely to lead to an increase of the global average temperature of around 2°C above the pre-industrial level.

And:

Given the serious risk of such an increase and particularly the very high rate of change, the Council believes that global average temperatures should not exceed 2 degrees above pre-industrial level and that therefore concentration levels lower than 550 ppm CO2 [carbon dioxide] should guide global limitation and reduction efforts. This means that the concentrations of all greenhouse gases should also be stabilized. This is likely to require a reduction of emissions of greenhouse gases other than CO2 in particular CH4 [methane] and NO2 [sic; nitrous oxide].

Ironically, it was inconsistent on the one hand, for the EU Council to advocate for carbon dioxide to be stabilized at or below 550 ppm with emissions eventually dropping to less than 50% of 1996 levels, while on the other hand, arguing for the 2°C threshold not to be exceeded.

While ambitious goal-setting can in theory be an effective motivator of action (Locke and Latham, 2002), in practice, alarmist media reframing (Ereaut and Segnit, 2006) of failure to remain below the 1.5°C goal into a scenario of impending doom has become quintessential fuel for personal climate anxiety. Taken in the collective across society, climate anxiety driven by personal concern and amplified by poorly calibrated media messaging is quickly emerging as a dominant factor in the collective zeitgeist of the Anthropocene (e.g. Crutzen 2006, Hickman et al 2021, Wray 2022).

Given that most of today’s decision-makers will not be around to be held accountable for their action, or lack thereof, towards meeting various targets set well into the future, a more appropriate framing and scientifically justifiable statement is for society to collectively do what we can to avoid as much warming as possible. Every tenth of a degree warming avoided reduces our collective climate risk and, by corollary, our overall collective climate anxiety.

But this still doesn’t address how individual climate anxiety can be reduced.

A far more constructive approach would be for the scientific community to turn our collective attention to climate solutions, not climate fear mongering or climate alarmism. Take the recent viral Tik Tok video showing Nasa Scientist Dr. Peter Kalmus prior to getting arrested after chaining himself to a JP Morgan Chase building in Los Angeles. The emotion in Dr. Kalmus’ voice indicates that he is likely dealing with his own climate anxiety, but I question whether or not the message in his viral video did anything more than increase the level of anxiety within children and youth worldwide:

“So, I am here because scientists are not being listened to. I am willing to take a risk for this gorgeous planet. That sucks, and we’ve been trying to warn you guys for so many decades now we are heading towards a catastrophe. And we are being ignored, the scientists of this world are being ignored, and it’s got to stop. We are going to lose everything, and we are not joking. We are not lying; we are not exaggerating. This is so bad everyone that we are willing to take this risk and more and more scientists, and more and more people are going to be joining us. This is for all the kids of the world — all of the young people, all of the future people. This is so much bigger than any of us. It’s time for all of us to stand up and take risks and make sacrifices for this beautiful planet that gives us life.”

At no point were any solutions posed, any positive actions suggested, or any personal climate risk reduction advocated for. The scientists involved likely believed that they were raising public awareness of the seriousness of global warming. Yet I argue that these same scientists abdicated their position of power and privilege by inadvertently pretending to be on the same footing as those most affected by climate change. In doing do, the scientists did little more than stoke the fires of climate anxiety when they had agency to facilitate constructive change both within their public engagements, as well as their own personal choices.

It’s also long been known that fear based messaging does not work in terms of motivating personal climate action (e.g., O’Neill and Cole (2009) , Stern (2012), Climate Tracker (2017). In fact, many simply disassociate themselves from the issue. Others, of course, take the fear to heart and it feeds their underlying climate anxiety.

Articles like McKay et al., 2022, with provocative, if not highly speculative, titles may attract media attention in the lead up to an annual UNFCCC COP event. But they are often framed as opinion or expert assessment and so are often highly controversial and not representative of broad scientific consensus. Extremely low probability, perhaps even impossible, but certainly poorly understood tipping point scenarios often end up being misinterpreted as likely and imminent climate events. The nuances of scientific uncertainty, the differences between hypothesis posing vs hypothesis testing, and the proverbial “implications of this work” throw away statements, wherein scientists take creative license with speculative possibilities, are all lost on the lay reader as the study goes viral across social media.

More recently, some activists have even called on the scientific community to engage in more civil disobedience (e.g., Capstick et al., 2022, Earth.org, 2022) arguing that it is effective and leads to change. Once more, I am not sure how activist scientists with agency help advance the necessary solutions and believe that the time for such activism has long passed. Governments around the world have committed to climate action but are struggling to advance the various solutions required for the low carbon economies of tomorrow. They need help, ideas, solutions and ongoing support and the scientific community is ideally positioned to assist in this regard.

In fact, many look to the climate science community for leadership on greenhouse gas mitigation and do so with dismay when they see these same scientists jetting off to various conferences, UNFCCC COP/IPCC meetings and workshops at exotic locations around the world. How many thousands of people attended the 26th Conference of Parties meeting of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in Glasgow in 2021? How many attended the 27th meeting in Sharm el-Sheikh in 2022? Was their presence really necessary? Climate scientists, with their privilege and agency, not only have a responsibility to assist identifying and implementing climate solutions; they also need to model the climate leadership they are calling on others to follow. Failing to do so sends the wrong message, a message that undermines the prevailing narrative that we are in a “climate emergency”.

More effective ways for scientists to advocate for climate policy

The climate science community operates from a position of privilege in the public discourse of climate change science, its impacts and solutions. Whether it be by participating in the writing of IPCC reports or our own research, climate scientists have defined the scale of the global warming challenge, outlined pathways to decarbonization of our energy systems, and documented a suite of future impacts, many of which would be very detrimental to future societies. We’ve also quantified the climate risk to our natural and built environment. Armed with this knowledge, climate scientists, more than most, are well-informed and so have agency in the advancement of climate solutions. But when climate scientists participate in civil disobedience or do little more than criticize others for inaction, they abdicate that position of privilege and agency by pretending to be on the same footing as others in society who are not as well informed on the nuances of climate change. As such, rather than alleviating their own, and broader society’s, climate anxiety, they fuel it further by inadvertently ratcheting up the rhetoric with nothing to offer in terms of overall solutions or risk reduction. I firmly believe that the climate science community has a duty and responsibility to become more actively engaged in the delivery of climate solutions in whatever form they feel most comfortable work with (i.e., nature-based, technological, socioeconomic or policy solutions).

At the same time, the scientific community must be reminded that they are but one stakeholder in the global warming debate. Whether or not society wishes to respond to the challenge of global warming really boils down to one question. Do we the present generation owe anything to future generations in terms of the quality of the environment we leave behind? Yes or No? Science cannot answer this question; but it can help articulate the expected consequences of action or inaction. Science can also inform decision makers by pointing out that if the answer to the above question is yes, dramatic GHG reductions (both through the decarbonization of energy systems and the introduction of negative emission technology) must commence now. Waiting until the future to start reducing emissions means waiting until it is too late.

While the answer to the above question is fundamentally personal, most almost certainly would respond yes, particularly those who have children. Yet some would disagree. For example, “Some evangelicals argue that global warming is of little concern when the end times are approaching. Indeed, it could even be proof of it” (Gander, 2019); Fatalists may believe that what will occur in the future is inevitable, perhaps even a manifestation of God’s will, and so believe that an individual’s actions or choices will have no effect on the direction we are heading. Libertarians may focus on the importance of individual freedoms, express concern about government overreach and regulation and may advocate for a laissez-faire approach to climate policy. There might be some who might answer yes to question, but their deep suspicion of environmentalists may make them question the urgency of dealing with global warming. Then of course there are those who will have been swept up in the various conspiracy theories so prevalent on the internet these days. Fortunately, the Pew survey cited above (Bell et al., 2021) allows us to estimate that it is only about 20% of the population who will likely object to the advancement of climate policy. And so, I am of the firm belief that engaging with this audience is counter-productive and a waste of a climate scientist’s time.

Instead of trying to persuade the unpersuadable, participating in civil disobedience or publicly demanding government take unspecified actions it would be far more productive if the scientific community, turned their attention to the development and advancement of climate solutions. This can be accomplished in any one of a number of ways. For example:

- Supporting progressive government policy vocally and publicly once it has been introduced;

- Running for office;

- Advocating for constructive solutions in recognition that we have agency and we occupy a position of privilege in society.

Given the emergence of social media in this post-truth age we are seeing more and more populist policies globally wherein decisions are made first, and then evidence (real or imagined) is sought after the fact to support an ideological agenda — this is what I call decision-based evidence-making, the antithesis to the scientific method. Scientists are driven by the quest to understand the world around us. We are driven by evidence. We identify problems and then take steps to solve these problems using reproducible techniques. Central to who we are as scientists is the notion of evidence-based decision-making. We understand this notion and react strongly to decision-based evidence-making, the antithesis to the scientific method. I truly believe our community has an inherent responsibility to exhibit the necessary leadership (especially through our own behaviour) to ensure that we play a constructive role in identifying solutions to the environemental problem that we have spent so many decades studying.

Finally, a co-benefit our community will warmly welcome in the move towards a climate-solutions focus, is the amelioration of our own climate anxiety (not to mention broader societal climate anxiety). I say this from personal experience, having worked in the field since the 1980s. Climate scientists, like others in the general public, often also struggle with the notion of climate anxiety and grief. But unlike others in the general public, our community holds agency and a position of privilege in the global warming debate. Rather than denying this agency and privilege I am hopeful that as a community we will collectively rise to the myriad opportunities global warming has afforded us for constructive public engagement and the betterment of society.

In the weeks ahead, I hope to expand upon these initial ideas by offering more concrete examples of engagement and responding to any feedback coming my way from this post.

Thoughtful voices: Sacha Christensen, Mark Leiren-Young & Rishi Sharma

In 2012, as I started my journey to become the BC Green MLA for Oak Bay Gordon Head, I was only too aware of how difficult it would be to win against the incumbent, BC Liberal Ida Chong. I was running for a party that had never elected anyone at the provincial level anywhere in Canada. There were no “party lists” that we could draw from; there was no party “apparatus” to call upon; there was no real “election readiness” or “provincial strategy”. Each of the BC Green candidates had to organically grow their support from the bottom up. And we did so against difficult odds and without access to organization networks like those associated with the so-called BC NDP ground game. I believed that the pathway to victory involved vowing to do politics differently and promising to work with whomever formed government. Ultimately, this approach was successful and I was able to advance numerous bills working collaboratively with the BC Liberals (from 2013-2017) and then the BC NDP (from 2017-2020).

When we elect politicians to govern on our behalf, we are electing individuals who are each armed with a toolkit of life skills, experiences, qualifications and views. Ideally, each elected person has a complementary, rather than identical, set of tools in their tool kits. For when these complementary tools are spread out on the decision-making table, more creative, inclusive and thoughtful policy and solutions are built. But in my view, what is most important is that we elect individuals who recognize the importance of advancing lasting policy through good governance that transcends traditional partisan divides.

On October 15, we go to the polls in the next general local elections. While I have already voted in an advanced poll for a full and diverse slate of School Board and Council candidates, I wanted to highlight three remarkable individuals on my list. These individuals span the political spectrum, and exemplify what I look for in an elected leader. None of them are presently holding elected office and there are enough incumbents not running to ensure that new people must be at the Saanich Council and School District 61 Board tables. I provide my rationale as to why I voted for these three individuals to help others as they do their research on who they will support on October 15. I recognize the importance of name recognition in local government elections and perhaps by doing this, I might convince a few of you to reach out to the three candidates below to learn more about their compelling campaigns.

1) Sacha Christensen – candidate for SD61 Trustee.

Despite the apparent lack of attention given to school board elections, Trustees in School District 61 actually manage a bigger budget ($268 million for 2022-23) than do the Mayor and Council of Saanich ($222 million for 2022-23). Over the past year, School District 61 was rocked with controversy as two trustees were suspended and subsequently reinstated. The annual budget process was also not without its own public controversy as music and support services took a hit to make ends meet. Given the turbulence of the past year, and with Board Chair Ryan Painter, Angie Hentze, and long time Trustees Elaine Leonard and Tom Ferris not seeking reelection, it is important to elect individuals with demonstrated expertise and experience who understand the importance of a collaborative, as opposed to an adversarial, approach to good governance.

Despite the apparent lack of attention given to school board elections, Trustees in School District 61 actually manage a bigger budget ($268 million for 2022-23) than do the Mayor and Council of Saanich ($222 million for 2022-23). Over the past year, School District 61 was rocked with controversy as two trustees were suspended and subsequently reinstated. The annual budget process was also not without its own public controversy as music and support services took a hit to make ends meet. Given the turbulence of the past year, and with Board Chair Ryan Painter, Angie Hentze, and long time Trustees Elaine Leonard and Tom Ferris not seeking reelection, it is important to elect individuals with demonstrated expertise and experience who understand the importance of a collaborative, as opposed to an adversarial, approach to good governance.

After being told by one of my children that I should consider voting for Sacha, I decided to interview him to learn more about why he was running to be a School Board Trustee at the age of 24. I was extremely impressed by his maturity, thoughtfulness and profound insight into civic and school politics.

Sacha graduated from the challenge program at Esquimalt High School and has completed his first two years of political science at Camosun College. For the past three years he has been working as the constituency assistant in Randall Garrison’s MP office. Constituency assistants play a critical non partisan role in an MP or MLA office. They are the front line staff who interact with and help constituents access the services available to them. As such, they are the public face of an MP or MLA in many community interactions. They should be unconditionally ethical and trustworthy, articulate, have exemplary interpersonal communication skills, hard working, intelligent and empathetic. It became quickly obvious to me why Randal Garrison had hired Sacha.

I asked Sacha why he chose to run to become a Trustee. He pointed out that the present make up of the Board was closer to retirement than to being back in school and that he felt it was critical to ensure students were always front and centre in School Board decision-making. He expressed concern over the 49% 5-year (57% 6-year) indigenous graduation rate in the district and the emergence of the VIVA slate of candidates who he did not believe shared his values. We talked about the lack of funding for students with diverse abilities and the troubling provincial model of education funding. I came away with the impression that Sacha was an exceptionally pragmatic thinker who understands how to advance policy solutions by bringing people together.

In summary, I am very impressed with Sacha Christensen’s collaborative approach to politics, as well as his perspective as a young candidate. I believe he has the expertise and experience to restore good governance to our school board.

More information on Sacha Christensen’s quest to become a Trustee in School District 62 is available on his campaign website.

2) Mark Leiren-Young — candidate for Saanich Council

I first met Mark many years ago when he came to interview me at my office at the University of Victoria. Mark was doing a podcast series on trees and I had just completed my book: Generation Us – The Challenge of Global Warming. We hit it off right away.

I first met Mark many years ago when he came to interview me at my office at the University of Victoria. Mark was doing a podcast series on trees and I had just completed my book: Generation Us – The Challenge of Global Warming. We hit it off right away.

A few years later, I once more bumped into Mark on the set of Wes Borg’s live comedy show, Derwin Blanshard’s Extremely Classy Sunday Evening Program, a show that I had become a regular on before I got elected. He sang “Kumbaya” as I proceeded to “beat the character of an Irish ambassador to Canada“, who was cast as a rabid climate change denier on the show, with a large “Nobel prize” prop! It was good-natured humour and Mark and I saw each other in different lights! It was also the last show I did before getting elected! And then in 2017, Mark interviewed me again in the final days of the 2017 provincial election campaign just prior to our historic election result, wherein the BC Greens were afforded the balance of power in the 2017-2020 BC NDP minority government.

Mark has been surrounded by politics his entire life. His mother met his father when she was running for Vancouver City Council and he was covering it for The Vancouver Sun. His father went on to become the legislative reporter for The Sun and then Bill Bennett’s press secretary. Mark also covered politics as a journalist for years and – among other gigs – used to write for a magazine called Trade and Commerce where he helped translate municipal business plans into plain language to draw businesses and investors to municipalities throughout the lower mainland. He was approached about becoming the city hall columnist for a couple of Vancouver’s better media outlets. And he started writing for the Monday Magazine while he was still a UVic student.

Mark is an exceptionally gifted artist and communicator. He’s won numerous awards for his books, television, theatre and film productions and teaches in University of Victoria’s creative writing department. Virtually all of his work, including some of my his commercial work, has involved social or environmental themes. Mark is creative, collaborative, innovative, pragmatic and understands how to work across partisan divides to advance inclusive policy for our community.

More information on Mark Leiren-Young’s quest to become a Saanich Councillor is available on his campaign website.

3) Rishi Sharma — candidate for Saanich Council

Rishi and I got to know each other in the 2013 provincial election campaign. He was the BC Liberal candidate for the riding of Saanich South and was running against my friend and colleague (from my days in the legislature), Lana Popham.

Rishi and I got to know each other in the 2013 provincial election campaign. He was the BC Liberal candidate for the riding of Saanich South and was running against my friend and colleague (from my days in the legislature), Lana Popham.

While I first met Rishi during an in-studio CFAX 1070 interview/debate early in the campaign, I got to know him better following an all candidates meeting that we we both participated in. Organized by the BC Sustainable Energy Association, this was a packed public event held at the Fernwood Community Centre on the theme: Energy and Climate. Rishi represented the BC Liberals. Rob Fleming (NDP), Duane Nickull (BC Conservatives) and I (BC Greens) were our party nominees. To no one’s surprise, the audience was not particularly warm towards the incumbent BC Liberal government. Yet it was clear to me why the BC Liberals sent Rishi to represent them. He was a compassionate listener and a thoughtful speaker.

What also struck me early on about Rishi was the respect, ethics and integrity he brought to his election campaign. We were both representing different political parties, yet we were both able to converse in a collaborative way. We focused on our shared values and spoke about how we could advance creative solutions to the issues facing the province. And over the decade since we first met, I have followed Rishi’s work within the BC Government.

What also struck me early on about Rishi was the respect, ethics and integrity he brought to his election campaign. We were both representing different political parties, yet we were both able to converse in a collaborative way. We focused on our shared values and spoke about how we could advance creative solutions to the issues facing the province. And over the decade since we first met, I have followed Rishi’s work within the BC Government.

Unlike many candidates running for local government positions, Rishi was born in, grew up in, and still lives in the community of Saanich. He attended Hillcrest Elementary, Arbutus Junior High and Mount Doug High School. His postgraduate studies include classes at UVic, Camosun and, more recently, Royal Roads university where he is finishing off his MA in Organizational Leadership. Rishi was also an accomplished athlete, playing soccer for Gordon Head, Metro Victoria and the BC Selects, while also competing in field hockey. He continues to give back to the community as a volunteer coash with Saanich Fusion soccer.

One of the things that most impresses me about Rishi is his deep insight into the needs of our community. He is pragmatic, principled, empathetic and respectful in all his work. He also brings business acumen to the decision making table.

More information on Rishi Sharma’s quest to become a Saanich Councillor is available on his campaign website.

Opportunity in Recovery: A Discussion of BC’s post COVID-19 future

On Wednesday June 17 we held a virtual town hall to discuss BC’s post COVID-19 future and answer any related questions. It was a very successful event and I grateful to the myriad participants for their thoughtful questions and comments. We’ve had a lot of requests for a copy of the video of the event and so I’ve reproduced it below for those interested.

I wish to offer sincere thanks to the panelists Katya Rhodes, Rob Gillezeau, Colin Plant, Emilie de Rosenroll and special guests Merran Smith and the Honourable George Heyman for their insightful contributions to the town hall.

Video of Panel Presentation

Opportunity in Recovery: Discussing BC’s post COVID-19 future

Join us on June 17 for a virtual town hall hosted by Dr. Andrew Weaver, MLA for Oak Bay-Gordon Head. Dr. Weaver will be joined by distinguished panellists Dr. Rob Gillezeau, Dr. Katya Rhodes, Colin Plant, and Emilie de Rosenroll to discuss BC’s post COVID-19 future and answer any related questions you may have.

Please confirm your attendance in advance by registering using the link below.

Register in advance for this webinar:

https://us02web.zoom.us/…/register/WN_QtJOU8iGRhKQT8a7kmr75Q

After registering, you will receive a confirmation email containing information about joining the webinar.

Panellist Bios:

Dr. Katya Rhodes is an Assistant Professor in the School of Public Administration and member of the Institute for Integrated Energy Systems at the University of Victoria. She investigates the topics of low-carbon economy transitions and climate policy design using survey tools, energy-economy models, media and content analysis. Prior to joining the academia, Dr. Rhodes worked in the British Columbia (BC) Climate Action Secretariat where she led greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions modelling and economic analyses for the provincial CleanBC plan.

Dr. Rob Gillezeau joined the Department of Economics at the start of 2016. Prior to joining the department, he served as the Chief Economist in the Office of the Leader of the Official Opposition in Ottawa. Dr. Gillezeau’s research applies causal methodology from labour economics to answer questions in modern American and Canadian economic history. His work has examined questions related to the interaction of the War on Poverty and the 1960s race riots, the growth of the North American trade union movement, and the role that the Transatlantic slave trade played in the development of ethnicity on the African continent.

In 2016, Emilie de Rosenroll became the inaugural CEO of the South Island Prosperity Partnership (SIPP). She spearheaded a number of economic development initiatives, including the regional Smart Cities strategy, involving over 50 organizations and including 15 local Governments. Drawing on her extensive governance and Public-Private expertise, the first phase of the strategy focuses on transportation and mobility followed by a focus on building common data platforms along with measurement of Mobility Wellbeing.

Colin Plant is a Saanich councillor where he serves as chair of the arts, culture and heritage committee and as chair of the of the Saanich LGBTQ sub-committee. He is also drama teacher at Claremont Secondary school and is chair of the Capital Regional District Board. Originally from Salmon Arm BC, Mr. Plant graduated from Stelly’s secondary in 1990 as the class valedictorian and has lived in Saanich for 15 years.

The opportunity for change in a post covid-19 economy

Today the Vancouver Sun published an opinion piece that I recently wrote.

Undoubtedly, the COVID-19 pandemic has introduced uncertainty into all echelons of daily life. But uncertainty need not inspire fear. Uncertainty is the precursor to innovation and innovation is the precursor to change. We are offered two choices today. To fear uncertainty and to fear change, or to see this generational challenge as a generational opportunity.

Below I reproduce the text of the opinion piece. The original is available on the Vancouver Sun website.

Text of Article

It’s been just over two months since BC declared a state of emergency in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and only a few days since relaxed restrictions were introduced in stage 2 of our provincial response. Yet judging from the myriad communications my office receives, British Columbians are still very nervous about the future.

While various commentators are suggesting we are heading into a “new normal” for business and, more generally, society as a whole, it’s far from clear what that “new normal’ looks like. Therein lies an incredible opportunity for the creation of long-term socially, environmentally and fiscally resilient and sustainable policies for British Columbia. For right now “uncertainty” seems to be the only thing “normal” in our daily lives.

Every challenge, whether it be global climate change, poverty reduction, the opioid crisis, the changing nature of work or even the COVID-19 pandemic, presents us with an opportunity for creativity & innovation; in other words, an opportunity to do things differently moving forward. For often the single biggest impediment to change is fear of the uncertainty that it will bring. Many entrench and defend themselves in the comfort of the status quo.

Jurisdictions that emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic stronger than before the deadly virus took hold will be those that adapt and respond in a timely fashion. Standing by and waiting for the holy grail of a vaccine or herd immunity, which may or may not ever occur, is simply not an option.

We are incredibly fortunate to live in British Columbia. Our provincial response to the pandemic to-date has been nothing short of exceptional. We’ve had calm, collected, evidence-based leadership by provincial Health Officer Bonnie Henry and Health Minister Adrian Dix. And most individuals and business have responded quickly to their requests, suggestions and orders.

As a direct consequence, British Columbia is now in a position to capitalize on the opportunities for change that the COVID-19 pandemic has created. But this will require an ongoing commitment to focus on the sage advice offered in a number of reports that were recently presented to the province.

On January 30, B.C.’s Food Security Task Force report was publicly released. “The Future of B.C.’s Food Systems” issued four recommendations designed to situate BC on an innovation pathway to capitalize on our strategic advantages in this sector. The report notes that the Netherlands ranks 131st in the world in terms of land area but is the world’s second largest exporter of agricultural goods. This is only possible because of the country’s focus on high value products, investments in innovation ecosystems, support for supply chain development, and strong land use policies. That’s what we should be doing in BC.

On May 11th the Emerging Economy Task Force final report was publicly released with 25 recommendations to assist British Columbia capitalize on global trends and technological advancements in the years ahead. That same day the final report from BC’s inaugural Innovation Commissioner, Dr. Alan Winter, was also publicly released. Dr. Winter provided five recommendations to government to encourage and assist the transformation of our economy to one that is resilient, based on our strategic strengths, and ready to lead in the 21st century.

And we will soon learn more from three distinguished scholars who are putting the finishing touches on their report exploring the role that basic income might play in reducing poverty and preparing for the emerging economy. A sneak peak of what we might expect from them appeared in an article entitled “Considerations for Basic Income as a COVID-19 Response” that was published Thursday by the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy.

A common theme in all these reports emerges. In light of the threat of pandemics, growing income inequality, and climate change, as well as the changing nature of work, modern economies need to quickly prepare. What has worked in the past will not work in the future.

As British Columbia emerges from the COVID-19 pandemic over the next year or so, we must learn from our mistakes and capitalize on opportunities that have arisen. The global shortage of protective medical equipment highlighted the importance of shoring up local supply chains and ensuring we have diversified manufacturing capacity locally. The complete chaos unfolding in the United States and Brazil as COVID-19 runs rampant there also underpins the importance of evidence-based decision-making in policy formulation.

British Columbia must also rethink its approach to the resource sector. Globalization has meant that we’ll never compete with jurisdictions that don’t internalize the social and environmental costs of resource extraction unless we are smarter, more efficient, cleaner and innovative in our extraction methodologies, and focus on value-added products for export. Sadly, our approach in recent years has been to literally give away our raw natural resources with little focus on the long-term effect this will have on the well-being and sustainability of rural BC.

British Columbia has three strategic advantages that set it aside from other jurisdictions around the world. 1) British Columbia is one of the most beautiful places anywhere to live. As such, we can attract to BC and retain the best and brightest worldwide because of the quality of life and the stable democracy that we can offer. 2) We have one of the best K-12 and postsecondary education systems in the world. They produce a highly skilled and educated workforce ready to meet the challenges of the 21st century. 3) We have boundless renewable resources in the form of clean energy, wood, water and agricultural land. And we have an economic plan embodied in CleanBC that recognizes these strategic strengths at its very core.

We should be using our strategic advantage as a destination of choice to attract industry to BC in highly mobile sectors that have difficulty retaining employees in a competitive marketplace. We should be using our boundless renewable energy resources to attract industry, including the manufacturing sector, that wants to brand itself as sustainable over its entire business cycle, just like Washington and Oregon have done in attracting a large BMW manufacturing facility and Google data centre to their jurisdictions.

We should be setting up seed funding mechanisms to allow the BC-based creative economy sector to leverage venture capital from other jurisdictions to our province. Too often the only leveraging that is done is the shutting down of BC-based offices and opening of offices in the Silicon Valley.

Undoubtedly, the COVID-19 pandemic has introduced uncertainty into all echelons of daily life. But uncertainty need not inspire fear. Uncertainty is the pretext to innovation and innovation is the pretext to change. We are offered two choices today. To fear uncertainty and to fear change, or to see this generational challenge as a generational opportunity. I prefer the latter and I’m excited to continue working with the BC NDP government in our attempts to capitalize on this opportunity.