Arithmetic

This post was written by my father, John Weaver, and originally published on April 5, 2016 on his blog: beorminga.wordpress.com. I am preserving them on my website as his blog posts are remarkable in their thoroughness and depth of research. Enjoy!

Arithmetic

Counting and arithmetic are a child’s first introduction to mathematics and would be regarded by those who go on to study algebra, geometry, trigonometry and perhaps calculus at high school as the most elementary branch of mathematics. Paradoxically, however, advanced arithmetic or number theory as it is usually called, is one of the most complex and difficult areas of mathematical research. It includes still unsolved problems that can be stated in simple-to-understand language and which appear to be true by trial and error, but which are fiendishly difficult to prove.

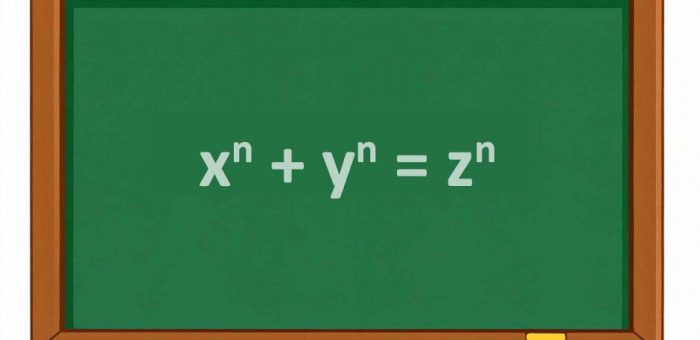

One famous example, of course, was Fermat’s Last Theorem, first postulated in 1637, but not proved until over 3 centuries later by Andrew Wiles. The theorem states that there are no positive integers x, y and z satisfying xn + yn = zn for integers n > 2 (that the equation has solutions for n = 1 is obvious and there is also an infinity of solutions for n = 2, for example 32 + 42 = 52, 52 + 122 = 132, etc.). Although no one could find a solution for n > 2 it took until 1995 to show that none existed.

p – 1, the first few of which are 3, 7, 31, 127, corresponding to p = 2, 3, 5, 7 respectively? Whether or not there is an infinity of them is still an open question even though the continual discovery of ever larger prime numbers of this type suggests they must be infinite in number (presently the largest one discovered corresponds to p = 74,207,281). Likewise, it is not known if there are infinitely many twin primes (prime pairs such as 11 and 13 that differ by 2) or perfect numbers (numbers such as 6 or 28 that equal the sum of their divisors excluding the number itself), nor indeed if there are any odd perfect numbers. Seemingly simple problems, but no solutions yet.

In the accompanying note Foundations of Arithmetic I mainly discuss the Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic. Although it is the basis of elementary arithmetic, it is related in its analytical form to the Riemann zeta function thereby showing how arithmetical problems can lead one straight into advanced analysis. That to me, as a total non-expert, is one reason why number theory seems such a fascinating subject requiring very special mathematical insights. I can understand why it is an area of research that has always attracted some of the world’s most gifted mathematicians.

The topics of Legendre’s formula, congruences, modular arithmetic, the totient and Euler’s theorem are also treated. The article concludes with a discussion of RSA encryption, a surprising application of what has always been regarded as the purest branch of mathematics with virtually no practical use. It has turned out to be of great importance, however, in protecting the security of the internet and electronic data transmission.

This is all thoroughly well-known material, of course, expressed here in my own style and notation. The books The Higher Arithmetic (Hutchinson, 1952) by H. Davenport, An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers (Oxford, 1960) by G. H. Hardy and E. M. Wright, and Number Theory (Oliver & Boyd, 1964) by J. Hunter were my principal sources of information. For the section on encryption, I found various postings on YouTube helpful.

Leave A Comment