Issues & Community Blog - Andrew Weaver: A Climate for Hope - Page 155

Bill 23(46): A Multigenerational Sellout as a Final Act of Desperation

Today in the Legislature we discussed Bill 23, The Miscellaneous Statutes Amendment Act at the committee stage. As I noted earlier, the bill contained a profoundly troubling Section 46 which granted the Minister unparalleled powers to enter into secret deals with LNG companies concerning natural gas royalty rates. At second reading I outlined my concerns in detail. Bruce Ralston, NDP MLA from Surrey-Whalley, and I supported each other, including our amendments, as we unpacked the implications of this bill. Below is the text of some of my contributions. I also provide a link to the Hansard video for Part I.

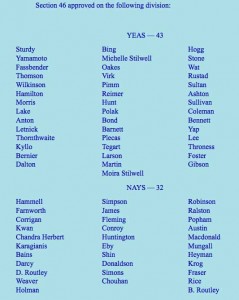

In the end both of my amendments as well as Bruce Ralston’s amendment were defeated. All members of opposition voted against section 46 as detailed below.

Video of Part I

Transcript of Part I

A. Weaver: Now, I recognize that government is rather desperate to land the $30 billion investment, and in so doing, we’re just seeing a $1 billion investment walk from Vancouver Island EDPR and TimberWest trying to put a billion-dollar wind farm investment…. Of course, government is not interested in that, because they’re desperate to fulfil this pipedream.

The concerns I have here…. I’ll ask a very direct one. In light of the fact that everything is up to the minister’s discretion, in essence, to enter into secret deals — presumably handed to him or her by a company, because this government has lost all credibility on this particular file — one of the things that they might do, for example, is work out a royalty rate that might actually be $1 billion less than it would otherwise be so that the company could then find a billion dollars to perhaps give to the First Nation to get title over their land. This is the kind of stuff that the public does not trust government on because of this legislation, where there’s nothing that precludes government working out a back deal to say: “Well done. Good for you to get your title rights recognized. Good for you to negotiate a cost. But we in the province of British Columbia will pay that cost, and we’ll pay that cost by changing this royalty rate in secrecy so that the company doesn’t actually pay it.” The province of British Columbia pays it.

My question to the minister is this, why does he need this level of secrecy, this level of secrecy here that he does not even need to give the Lieutenant-Governor-in-Council, his cabinet colleagues, notification as to what deals he is making? Does this minister honestly believe that the millions of people living in British Columbia trust him and only him to negotiate royalty rates for generations to come because somehow he knows what’s going on, and no one else does?

Hon. R. Coleman: I will walk past the ignorance of the question and just go to my answer. If the member would look and do some research with regards to the legislation, the power given to the minister to do this comes from Lieutenant-Governor-in-council, which is cabinet — the ability to do this. And if there’s any change in revenues or things that have to be adjusted on a financial basis, the minister, as I know, with regards to my service plan, my letters of expectations with my responsibility to government…. Anything that affects the government fiscally, I have to take back to Treasury Board.

I think it’s inappropriate for the member to think that it’s just the minister that’s making this decision. In addition to that, if the member would like to look at section 78.1, subsection (3), it also says that “The minister must, as soon as practicable, publish an agreement entered into under (1) but may withhold from publication anything in the agreement that could be refused to be disclosed under” — an act that governs us all — “the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act.” The only thing that would be not disclosed in that, I believe, would be if there was something that was significantly different or something that was — technology over whatever — with regards to the design of a plant or something that may have an effect on the competitive side or the marketplace before it was disclosed by the company in the appropriate manner.

If a request were made under that act, the disclosure of the agreement has to take place. It’s our full intent to make these agreements public.

A. Weaver: Well, in fact, I have read this legislation rather carefully. I’ve been following this file very carefully for the last two years. Frankly, what I’ve been saying for all that time is playing out here. Here’s another sellout.

In fact, if you read 78.1(2), it says the following: “The approval of the Lieutenant Governor in Council is not required for the minister to enter into an agreement under subsection (1)….” I don’t know what the minister doesn’t see about that, but it specifically says that “the Lieutenant Governor in Council is not required for the minister to enter into an agreement under subsection (1) (a) in the prescribed circumstances, or (b) in respect of a prescribed class of agreements.”

In essence, this is saying that the minister can essentially enter into an agreement…. The province of British Columbia, all of us, believe that we have such confidence in this minister that we are going to let him — and only him — go into an agreement with a multinational corporation. This has got to be some kind of a joke.

What is the justification that the minister needs these exclusive powers to go and enter into agreements without his cabinet colleagues knowing, without the Premier having to even know, but giving him power under section 78.1(2) to do this? What gives him the right? This is not an autocracy. Why does the minister think it is?

Hon. R. Coleman: If you read the section, it says: “in the prescribed circumstances, or (b) in respect of a prescribed class of agreements.” These are determined by Lieutenant-Governor-in-Council and allow the minister to sign them as a delegated authority to do so.

The characteristics of these agreements — in prescribed circumstances and in the class of agreements — are dealt with long before they’d ever get to an agreement with regards to what’s in them and what the minister can sign or cannot sign.

So basically, what it effectively does…. It does what most pieces of legislation do and delegates authority, after certain prescriptions and outlines have been prescribed by government, to a minister that he can execute on behalf of government.

Video of Part II

Transcript of Part II

A. Weaver: Coming back to section 46, section 78.1(2)(a) and (b) where it describes: “The approval of the Lieutenant Governor in Council is not required for the minister to enter into an agreement under subsection (1) (a) in the prescribed circumstances, or (b) in respect of a prescribed class of agreements.”

The minister recently said that the type of agreements that he or she or whoever the minister will be can enter into are controlled by cabinet. But we have no indication as to what “prescribed circumstances” are. We have no indication as to what “prescribed class of agreements” are.

It could be — and I seek confirmation from the minister — that a prescribed class of agreements could be any agreement to extract natural gas from the Montney region in British Columbia and export it anywhere in Asia. That’s one possible interpretation, and “under the prescribed circumstances,” that the minister has the time to do so. Essentially, this would grant the minister…. We have no sense of this.

Is what I just said precluded from that? What constraints are being placed on the minister to enter into these agreements without consulting, without the need for the Premier, without the need for cabinet, without the need for anyone, obviously, except the proponent to know about what the agreement is? This set of prescribed circumstances and agreements is so large and vague, it could include anything.

Hon. R. Coleman: It gives to the Lieutenant-Governor-in-Council, in prescribed circumstances or in respect of a prescribed class of agreements, to allow the minister to execute them. Those will be prescribed in regulation through Lieutenant-Governor-in-Council, not arbitrarily by the minister.

A. Weaver: I guess that’s my point. I reiterate what I said earlier. In light of the fact that this government is so desperate to sign agreements with now one company — it’s, I guess, given up on a number of others — there is a lack of trust. There’s a lack of trust that this section is not going to be anything more than “prescribed class of agreements” is with Petronus, for example, or with any company involved in the Montney play that wants to sell gas to Asia. So there is a great deal of uncertainty with this.

This amendment does simply not instill confidence in British Columbians that the government actually has any sense of direction or actual clue as to what they’re doing. They’re making it up as they go along, moving it from a generational to now, as my friend from Nanaimo–North Cowichan points out, a multigenerational sellout in a desperate attempt to try to land a company.

Let me just follow up with a direct question here. If the minister signs an agreement under subsection (2) and then after giving it to the Lieutenant-Governor-in-Council — now it’s signed — the Lieutenant-Governor-in-Council receive this, and they then determine that they don’t like it, that the minister overstepped his or her bounds, my question is: what ability does the Lieutenant-Governor-in-Council have to overturn an agreement that was signed by a minister under section 78.1(2)?

Hon. R. Coleman: I know that the NDP and the independents in this House don’t support liquefied natural gas as an industry for the future of the British Columbia. I know that. I know the member is clearly after that in his mind, and that’s fine.

But if the member will think about the legislation, it allows regulations to be developed that specify the circumstances or describe the types of agreements that the minister can enter into. Don’t get to write the agreements. The Lieutenant-Governor-in-Council actually prescribes that in regulation. And by the way, every week the decisions by the Lieutenant-Governor-in-Council on regulations are published. That information, in and around the agreements, would be published, and the minister could only execute under those terms. If he went outside those terms, because of the regulation being in place, it wouldn’t be a legally enforced agreement.

A. Weaver: With respect, this has nothing to do about being against or for natural gas. This has to do with economic folly and irresponsible promises by this government in an election campaign that they cannot fulfil. Here we see desperation in legislation. We see one after another as they so desperately try to land a single contract.

The reality is…. I’m going to read this again. I have read this legislation. It says as follows: “The approval of the Lieutenant Governor in Council is not required for the minister to enter into an agreement under subsection (1) (a) in the prescribed circumstances, or (b) in respect of a prescribed class of agreements.” It doesn’t say in respect to an agreement that has been reached and agreed to by cabinet already. It says in prescribed circumstances or a prescribed class of agreements, which is incredibly vague, no matter how you interpret that.

Again, to the minister. If he believes that these circumstances or agreements really curtail or constrain what he is able to sign, why doesn’t he tell us what they are? Why doesn’t he table here today what is actually meant by prescribed circumstances or a prescribed class of agreements? Right now it can be anything. Will the minister table examples of what these are?

Hon. R. Coleman: I’ll reiterate it. I do know the member opposite doesn’t support liquefied natural gas as a new industry for British Columbia. Even in that case, this is a piece of the legislation that allows for regulations to be developed that specify the circumstances that the minister could actually enter into and sign an agreement on behalf of the province of British Columbia.

The regulation is a law, hon. Member. The minister has to follow that law in those prescribed circumstances and in respect of the prescribed class of agreements. He has to do that, because that is defined in regulation. The regulation is developed when legislation is passed.

A. Weaver: Again, to correct the record, I have never said I am against liquefied natural gas. In fact, if you go back to estimates, you will see that I have been arguing strongly for promoting domestic sector use, including the use of liquefied natural gas in our ferry systems in British Columbia, long before the government actually came up with that direction and idea.

This is not about liquefied natural gas. This is about irresponsible economic outlook — that the government is going in with no financial underscoring. They seem to be the only ones in the world that believe this is going to play out, and they’re desperate to do so.

Coming back to the question. The reality is, as the minister would like us to believe, that somehow he’s going to be constrained in entering into these agreements, that the regulations will be developed after the fact.

There is no trust on this file anymore. So there is no trust. The government is simply not trusted to be acting in the best will of the people on this particular file. We’ve seen, time after time after time, broken promises, changing legislation. We bring in an act, an LNG act. We then completely change the LNG tax act only a few months later.

It’s for this reason that I have a second amendment that I wish to put here to actually add another check in place. This is on the order paper. It’s adding a section (8) to 78. So it’s 78.1(8), which says the following:

[SECTION 46, by adding the underlined text as shown:

(8) The Lieutenant Governor in Council may, without penalty, pull out of an agreement entered into under subsection (2) within six months of the time at which the minister provided the Lieutenant Governor in Council with the full text of the agreement.]

A. Weaver: The reason why I’m doing this is I don’t trust the minister. The opposition doesn’t trust the minister. The people of B.C. don’t trust the minister. International companies don’t trust the minister. The minister has no trust on this file.

Hon. R. Coleman: I guess he will have to understand what the law means with regards to regulation.

I should tell the member opposite that I spent eight years with the RCMP. You can’t throw an insult at me that’s going to bother me. So try as you must, it just isn’t going to work.

On the other side, the flip side, I know the member opposite doesn’t think that we have opportunities on liquefied natural gas in British Columbia. Like I said to him in debates of a while ago, I want to be invited to the dinner when he has to eat those words. It will happen in the not too distant future, I believe.

Over the next year or two, you’ll see a number of these projects go ahead. They’ll go ahead not because the international community mistrusts the minister. It’s because the minister has built a relationship with the industry across the world and with financiers to the fact that they actually believe this government will deliver on what it says it will do and, therefore, will come to B.C. and invest.

The Vote

Interview on BC1

Celebrating Mining Week in British Columbia

This week we celebrate mining in British Columbia. From May 3-9 events will be held across British Columbia to highlight the importance of mining to British Columbians.

B.C.’s mining industry is one of the pillars of our economy. In 2013, the year for which most recent data is available, the mining sector contributed $8.5 billion to BC’s GDP and employed 10,720 British Columbians. It further contributed $511 million in tax revenues to provincial coffers. Mining forms the backbone of many rural communities throughout the province, supplying us with the resources we need to enjoy the prosperity we are so fortunate to have in B.C.

Our mining industry continues to play a pivotal role in facilitating the transition to a 21st century economy. For example, without metallurgical coal, we cannot manufacture steel. Without graphite, we cannot build lithium ion batteries.

It is for this reason that I travelled to the Kootenays in April to learn more about the opportunities and challenges facing our Mining Industry in B.C. What follows is a brief report on two tours I did while I was there.

Teck Resources Ltd Metallurgical Coal Operations

Employing roughly 7,960 people and contributing $6.5 billion in gross mining revenue, Teck Resources Ltd is Canada’s largest diversified resource company, with many of its assets in metallurgical coal mining. I reached out to Teck Resources because I believe it’s important to have a clear understanding of British Columbia’s coal industry.

Employing roughly 7,960 people and contributing $6.5 billion in gross mining revenue, Teck Resources Ltd is Canada’s largest diversified resource company, with many of its assets in metallurgical coal mining. I reached out to Teck Resources because I believe it’s important to have a clear understanding of British Columbia’s coal industry.

Five of Teck Resources’ thirteen mines are located in the Elk Valley in the Kootenays where they extract metallurgical coal. While I was there, I had the opportunity to meet with representatives from Teck Resources and to tour their Coal Mountain operations.

Those who have read my previous coal-related posts know how important I believe it is to distinguish between thermal coal, which is used for coal-fired power plants, and metallurgical coal, which is used in the production of steel. Metallurgical coal is used to produce coke. This is done via heating the coal to very high temperatures (>1000°C) in the absence of oxygen. The resulting almost pure carbon is then mixed with iron ore to create the molten iron that is turned into steel.

Thermal coal, on the other hand, is the single biggest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions in the world. It is also the most widely available of all fossil fuels and we produce very little of it here in British Columbia. Thermal coal has smaller carbon content and higher moisture content that metallurgical coal thereby precluding its use in steel making.

Thermal coal, on the other hand, is the single biggest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions in the world. It is also the most widely available of all fossil fuels and we produce very little of it here in British Columbia. Thermal coal has smaller carbon content and higher moisture content that metallurgical coal thereby precluding its use in steel making.

The overwhelming majority of thermal coal that is shipped through British Columbia ports is sourced from the United States. That coal travels through B.C. ports because Washington, Oregon, and California have taken a stand to curb their own thermal coal exports. To quote from the governors of Oregon and Washington “We cannot seriously take the position in international and national policymaking that we are a leader in controlling greenhouse gas emissions without also examining how we will use and price the world’s largest proven coal reserves.” Here they were acknowledging that the United States has the largest reserves of thermal coal in the world (237,295 million tonnes) and that their domestic market is dropping as natural gas generation increases and more renewables are brought on stream.

Teck Resources produces metallurgical (not thermal) coal here in British Columbia. The fact is that metallurgical coal is essential for building everything from windmills to electric cars because without it, you cannot have steel. Teck Resources’ five metallurgical coal mines in the Elk Valley employ about 4,000 people and together contributed $140 million in taxes to the province in 2014. Touring Teck Resources’ Coal Mountain mining operation offered an excellent view into the scale and complexities of modern metallurgical coal mining in British Columbia. I was extremely impressed by steps Teck has taken to ensure their metallurgical coal operations were as environmentally sensitive as possible. These include their approaches to reclamation, greenhouse gas reductions, acquisition and preservation of parkland for future generations, and their state of the art water treatment operations that will commence in the Fall of this year.

Teck Resources produces metallurgical (not thermal) coal here in British Columbia. The fact is that metallurgical coal is essential for building everything from windmills to electric cars because without it, you cannot have steel. Teck Resources’ five metallurgical coal mines in the Elk Valley employ about 4,000 people and together contributed $140 million in taxes to the province in 2014. Touring Teck Resources’ Coal Mountain mining operation offered an excellent view into the scale and complexities of modern metallurgical coal mining in British Columbia. I was extremely impressed by steps Teck has taken to ensure their metallurgical coal operations were as environmentally sensitive as possible. These include their approaches to reclamation, greenhouse gas reductions, acquisition and preservation of parkland for future generations, and their state of the art water treatment operations that will commence in the Fall of this year.

Now, Teck Resources does not only produce metallurgical coal. They also own and operate Highland Valley Copper and the integrated zinc and lead smelting facility in Trail. If we actually include all of Teck Resources’ operations in our province, this one company accounted for 21% of all BC exports to China in 2013. That year Resources directly employed 7,650 full-time workers with an average salary of $100,000 per year. They are expanding their operations in British Columbia and presently there are 28 job openings within the company.

Eagle Graphite

Whereas Teck Resources is British Columbia’s largest mining company, many of B.C.’s junior mining companies are quite a bit smaller. Eagle Graphite Mine is one of them.

Whereas Teck Resources is British Columbia’s largest mining company, many of B.C.’s junior mining companies are quite a bit smaller. Eagle Graphite Mine is one of them.

Located in the Slocan Valley, Eagle Graphite is one of only two flake graphite producers in North America and the only one in British Columbia. Graphite is an essential component of lithium ion batteries, which are used in electric vehicles. In fact, about 95% of a lithium battery is made up of graphite. About 50 kilograms of graphite is contained in an electric car, 10 kilograms in a hybrid vehicle and 1 kg in an electric bike. Laptops and mobile phones contain about 100 grams and 15 grams, respectively.

Located in the Slocan Valley, Eagle Graphite is one of only two flake graphite producers in North America and the only one in British Columbia. Graphite is an essential component of lithium ion batteries, which are used in electric vehicles. In fact, about 95% of a lithium battery is made up of graphite. About 50 kilograms of graphite is contained in an electric car, 10 kilograms in a hybrid vehicle and 1 kg in an electric bike. Laptops and mobile phones contain about 100 grams and 15 grams, respectively.

By the end of the decade, graphite demand for electric vehicles produced in North America is projected to increase substantially, far exceeding current supply. The team at Eagle Graphite has been working hard to take advantage of this projected supply gap by proving their reserves and developing methods to efficiently extract graphite from their quarry reserves. And one of the interesting tidbits I picked up on the tour was that golf course grade sand is the by-product of producing graphite!

Touring Eagle Graphite offered a helpful insight into the opportunities and challenges faced by smaller mining firms.

Summary

My brief trip to the Kootenays highlighted the diversity of resource opportunities that have been capitalized upon in the area. What impressed me most at the locations I visited were the steps taken by all companies involved to ensure sustainability of their industry for decades to come with minimal environmental footprint. Whether it be Teck Resource’s Elk Valley coal operations or their Trail smelter powered by the Waneta Dam, Eagle Graphite’s small operation, Canfor’s Elko Mill, or Columbia Power’s Waneta Expansion Project, everyone I met was beaming with pride at the work that they do, their safety records, and the care they take to ensure their operations are as clean and sustainable as possible. After all, these people are locals and the industrial operations are literally in their backyard.

Finally, a highlight of my trip truly had to be that I can now say triumphantly “I’ve been to Yahk and Back”.

Soils in the Shawnigan Lake Watershed — Some Questions

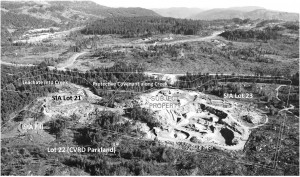

Earlier this month I wrote a piece on the wisdom of dumping contaminated soils in the Shawnigan Lake watershed. I visited the region with Shawnigan Lake Area Director Sonia Furstenau. Together with a few other Shawnigan Lake residents, we hiked around on parkland owned by the Cowichan Valley Regional District. I took this opportunity to take a number of photographs. More importantly, I took the opportunity to collect water samples.

Earlier this month I wrote a piece on the wisdom of dumping contaminated soils in the Shawnigan Lake watershed. I visited the region with Shawnigan Lake Area Director Sonia Furstenau. Together with a few other Shawnigan Lake residents, we hiked around on parkland owned by the Cowichan Valley Regional District. I took this opportunity to take a number of photographs. More importantly, I took the opportunity to collect water samples.

The results of these water samples, together with my observation that a significant amount of fill had over run Lot 21 and was on the neighbouring parkland, led me to ask the Minister of Energy and Mines and the Minister of Environment questions in Question Period today.

Below are the questions and the Ministers’ responses. I gave the Ministers my questions in advance as I wanted to give them time to check with staff prior to providing answers. The answers I received in my view are very helpful in providing information to the CVRD as to how they might proceed.

Question

A. Weaver: I have in my possession two letters [here and here] sent from the Ministry of Energy and Mines to South Island Aggregates in Shawnigan Lake concerning “sloughing or material that encroached onto Cowichan Valley regional district property.”

The April 1, 2014 letter from the ministry’s regional manager for the coast area states that “the property impacted by the encroachment must be cleaned up and returned to its pre-encroachment state to the satisfaction of the property owner.”

The story continues. I also have a letter from the CVRD clearly outlining the fact that the property impacted has yet to be cleaned up, let alone to the CVRD’s satisfaction. South Island Aggregates needs an amendment to its mines permit before its Ministry of Environment permit can become active.

Will the Minister of Energy and Mines commit to ensuring that before an amended permit is issued, the infractions and issues of non-compliance at this site have been addressed?

Answer

Hon. B. Bennett: It’s actually refreshing to get a question where the member has a good grasp of the facts. I don’t think that this quarry is in the member’s riding so, honestly, he deserves a lot of credit for having done the due diligence that whoever the MLA is for that area hasn’t done.

To the member’s question, he is correct that there was a commitment made by the Ministry of Energy and Mines that we would ensure that the company that had encroached on regional district land would, in fact, remediate that land. An engineering plan has gone to the regional district, about eight weeks ago.

I don’t know why we haven’t heard back from the regional district, but I will commit to work with the member, work with our ministry, work with the regional district and make sure that they know they have that plan. They can take some time to look at that plan, and that RD land will be remediated.

Supplementary Question

A. Weaver: Thank you to the minister for the answer.

For several years soil has been dumped in lot 21 for later use as backfill for the neighbouring quarry in lot 23, which we just discussed, where the amended permit is required. I recently visited the location. I collected and subsequently analyzed water samples and noted that runoff from this site entering Shawnigan Creek had extremely high iron levels that failed drinking water standards locally.

The Cowichan Valley regional district is very concerned about the long-term safety of drinking water in the Shawnigan Lake area. They want to conduct an independent environmental investigation of lots 21 and 23 and are willing to pay the costs of doing so themselves. There will be no expense to the government.

My question to the Minister of Environment is this. Does the CVRD require a contractual agreement with the ministry to allow them to conduct such an investigation? If so, will the ministry consider entering into such an agreement? If not, is it the minister’s understanding that the CVRD have full authority to conduct such an independent environmental investigation on lots 21 and 23?

Answer

Hon. M. Polak: Thank you to the member for providing some details ahead of time. That enabled me to pursue and seek some advice with respect to jurisdictional issues around environmental testing.

Here’s what I can tell the member. With respect to lot 21, it is private property. Now, that means for the Ministry of Environment that we have full authority to be able to enter that property, conduct testing, investigate if there are concerns with respect to pollution. We intend to do so. We have done so, and I will talk a little bit more about that in a moment.

There is, however, though, no authority — the minister possesses no authority — to be able to allow another party, even through a contractual arrangement, to engage in that kind of investigation on private land. Here’s what we can do, though. Staff, after meeting with representatives from CVRD have developed a sampling plan for the site. I understand they will be discussing that with CVRD today.

We cannot order the private property owner to allow CVRD members to attend and observe. However, we will be discussing that with them, and we’re hopeful that on a voluntarily basis the landowner will allow us to bring along CVRD representatives to observe the testing. In the absence of that we will certainly make sure that all test results, all test processes are discussed and shared with the CVRD.

Video from Question Period

Bill 11: Education Statutes Amendment Act, 2015

For the foreseeable future, it seems likely that British Columbians will have to watch as the decades long dance of dysfunction between the BC Government and the BCTF continues to play out.

The most recent iteration of this is taking place in the Legislature this week as we debate Bill 11 – The Education Statutes Amendment Act.

Sadly, with the introduction of this Bill we’ve missed out on an incredible opportunity for British Columbians to come together through an engaging discussion about how we might improve our education system.

In introducing Bill 11, yet another opportunity to rebuild the relationship between teachers and government has been squandered. The Bill unilaterally allows government control over the professional development of teachers, and empowers government to issue directives to school boards that they would be bound to follow.

I want to be clear – I welcome a conversation about reforms to our public education system. We need to be willing to discuss controversial topics like re-examining the role school boards play in a modern education system and whether a decade of corporate and personal income tax cuts have gone too far.

However, these much needed conversations can only take place when all those involved demonstrate a commitment to their relationship with one another, and actively seek to build mutual trust and understanding. And while Bill 11 is only the most recent example of governments role in damaging this relationship, the BCTF is not without responsibility. Earlier this year the BCTF invited the Leader of the BC NDP to address their 2015 AGM in a partisan speech that ended with him calling on everyone to defeat the BC Liberals. This does nothing to build bridges. Rather, it further deepens the partisan divide and everyone loses when that happens.

It is easy to forget that amidst all these issues, British Columbia is home to outstanding teachers and a world renowned education system. We should be celebrating our successes and supporting the good work being done by teachers in our province.

Bill 11 is a poorly thought out piece of legislation that deserved a far more rigorous and substantial public consultation so that we could have the conversation about public education that we need. I will not be supporting its passage and will continue to work to establish a different way forward on public education.

A full copy of my remarks can be found below.

Video of Second Reading Speech

Transcript of Second Reading Speech

To begin, I’d like to emphasize that I’ve always believed that teaching is the single most important profession in our society. Each and every one of us has attended school, and that experience has shaped who we are, what we do, and how we contribute to society. So it follows that public education represents perhaps the most important investment government can make for the prosperity of our province.

Public education is absolutely critical in teaching the next generation of British Columbians to think critically, contribute responsibly to society and to become the leaders of tomorrow.

Teaching is a thoroughly rewarding, yet physically and emotionally exhausting profession. It takes a very special person to be able to instruct a class of 20 to 30 young children for five hours every day. Last year I spent a day engaging every grade from kindergarten to grade six at Savory Elementary’s Four Seasons Eco-School (4EST) program.

I only had one lesson plan to deliver to the seven separate classes, from 8:45 to 2:30 on that day. I had no marking to take home, no report cards to write, no parents to interact with, no staff meetings and no administrative activities. Nor did I have to take the students on extracurricular activities. But let me tell you that I was exhausted at the end of the day. And I only did that once, not day in, day out, for months on end.

Let me start my speech by noting that we have outstanding teachers and an exceptional education system in the province of British Columbia. Every three years the Programme for International Student Assessment, known as PISA, evaluates the performance of students internationally in three subject areas: mathematics, science and reading.

The Council of Ministers of Education, Canada further breaks down the Canadian results on a province-by-province basis. British Columbia consistently performs extremely well. In 2012, for example, British Columbia was the top Canadian province in reading and science and was second only to Quebec in mathematics.

In fact, British Columbia students even performed better than students from the much-touted education system in Finland in both reading and mathematics. And while Finland scored slightly ahead of B.C. in science, the difference was statistically insignificant. Of course, we’ll have to wait until December 2016 to get the PISA 2015 results to see how British Columbia continues to fare.

Now, I recognize that the PISA results only provide one metric of student achievement and, hence, the success of the British Columbia school system. Nevertheless, it’s a very positive one. It says to me that we must be doing something right in British Columbia despite what we might read about in the news. It also suggests to me that maybe we should start to celebrate our successes and dwell less on the negative arising from a dysfunctional relationship between the B.C. government and the BCTF.

At the end of the strike last fall the government spoke about “an historic six-year agreement…which means five years of labour peace ahead of us.” Rather than viewing this as five years of simmering anger waiting to boil over when the negotiations next begin, we should be capitalizing on this time to envision bold new ways of ensuring our educational system is sustainable.

This includes teachers being fairly compensated and adequately supported with properly funded curriculum and learning resources. Such support must include sincere and meaningful class size and composition discussions and support that recognizes that teacher burnout affects us all. It must include reinvigorating our educational infrastructure and ensuring that children have textbooks and access to learning materials.

On Thursday the B.C. Court of Appeal will release its decision concerning the rights of teachers to negotiate conditions around class size and composition. Rather than allowing this to serve as a catalyst to incite increased tension between the BCTF and the government, perhaps both parties will recognize the opportunities that will arise from mutual collaboration, no matter what the Court of Appeals decision is.

For example, perhaps there is a compromise on class size and composition negotiations. Why don’t the BCTF and the B.C. government both agree, for example, that the best place to negotiate class size and composition is at the local school district level?

In fact, as noted in the book Worlds Apart: British Columbia Schools, Politics and Labour Relations Before and After 1972 by Thomas Fleming, the BCTF was not pleased with the 1994 Public Education Labour Relations Act which led to the formation of BCPSEA and the BCTF being appointed as the official bargainer for all teachers.

Provincial data clearly show that one size does not fit all. The class-size and composition needs of Haida Gwaii school district 50 are almost certainly different from those in the Gulf Islands, No. 64, or Surrey, school district 36.

Perhaps both parties would consider waiving the right to strike in favour of binding arbitration with respect to salary and benefit negotiations. In 1950 Manitoba teachers did just this. In return, they gained binding arbitration, due process and a provincial certification board. There has been labour peace in Manitoba ever since.

Binding arbitration forces each party to come up with their best offer. The arbitrator then chooses from one of them or some combination of both. One thing is certain. Outlandish requests are taken off the table quickly when binding arbitration is in play.

While the B.C. government and the BCTF play out their decades-long dance of dysfunction as they battle it out, entrenched in what I perceive to be ideological positions, the ones who are paying the price are the children in the classroom, the teachers who teach them, and their parents at home.

But moving this relationship forward requires trust, mutual trust. It’s easy for me to see why the BCTF and other stakeholders in public education are leery to trust the direction this government is taking in Bill 11. This bill is a classic example of putting the cart before the horse. Rather than engaging education stakeholders in meaningful dialogue, the government is providing itself with rather sweeping powers to appoint special advisers and issue administrative directives. Nobody knows what the minister has in mind or what cabinet will do with these powers, should this law receive royal assent.

Bill 11 repeals the concept of school planning councils. Frankly, I support moving back to focusing the parent’s role in the parent advisory councils. The B.C. Liberals school planning council model was a failed approach to school-based governance, introduced when our current Premier was the Minister of Education.

I doubt that there will be much public outcry over this, although it would have been preferable to give the public more opportunity for input prior to actually putting this legislation forward. After all, this is public education that we are discussing here today.

Bill 11 takes the very provocative and, honestly, I think, ill-thought-out position of empowering the minister to set teachers’ professional development requirements. Like any profession, teachers require ongoing professional development. That goes without saying. But like these same professions, professional development must be led by the experts. In this case it’s by the teachers, not by ministerial decree.

Now, I recognize that the minister will say and respond that he wants to negotiate with the BCTF as to what this professional development might look like. However, my reply to the minister on this is that he’s lost trust. He’s lost the trust of the teachers, as what the minister had in mind should have been conveyed prior to, rather than after, this legislation being tabled.

Besides, what body would oversee the professional development? The B.C. College of Teachers would have been the natural place, but it’s been disbanded. The BCTF is a union tasked with representing its members in negotiations, not in maintaining professional standards. So they are not the appropriate home for such professional ongoing professional development.

The teacher regulation branch doesn’t seem the right place either. So what does the minister have in mind? We simply don’t know, and therein lies the problem. Why are we bringing forward legislation to discuss this when we do not know what the minister has in mind and when trust has been broken and lost with negotiations on this topic with the teachers before we’ve even started to discuss it?

It’s clear to me that this bill was not ready for debate in the Legislature. In my view, it should have followed the lead of the Society Act or the Water Sustainability Act and allowed extensive public consultation prior to its introduction, rather than afterwards.

Both of those pieces of legislation obtained a social licence, public support. In the case of the Society Act, public input led to a better act, with the removal of section 99. But here we do not have public support. We’ve just come off a prolonged strike, and on Thursday the B.C. Court of Appeal will release its long-awaited decision.

What an incredible opportunity this could be for British Columbians to be offered to come together through an engaging discussion about how we might improve our education system.

Instead of discussing this ill-thought-out legislation whose direction is not actually brought forward with any substance today for us to speak to, we could have had a discussion about education. For example, we could have had a discussion about education funding.

The level of funding allocated to our public education system depends on the priorities of the government. In British Columbia spending on health care has remained a priority since 2000, ranging between 7 percent and 8 percent of provincial GDP. Funding for social services and education expressed as a percentage of GDP, on the other hand, has dropped over this period of time.

In the case of education funding as a percentage of provincial GDP, it has declined from a high of about 6.4 percent in 2001-2002, when the Liberals took office first, to an estimated low of about 5 percent in 2014-2015. Now, that’s a 22 percent decline in the percentage of funding, as a percentage of GDP, being spent on education in our province.

If British Columbians deem education to be as important as I do, surely this drop needs to be rectified. So the question is: where does this money come from? I would argue that British Columbians need to have a hard look at our sources of provincial revenue and the way we spend the money that government receives. Given a decade of corporate and personal income tax cuts, perhaps it’s time to take a look at whether or not we’ve gone too far.

That’s an important discussion to have, as it ultimately affects the availability of funds for our public education system. That’s a discussion we could have had prior to the introduction of Bill 11. With increases in public school enrolment looming, it’s critical that we initiate this discussion now, not later, not tomorrow, not after the next settlement is in negotiation with the teachers in our province.

We could have had a discussion about the ongoing role of the B.C. Public School Employers Association. The BCPSEA was established in 1994. Since that time there has been a continued escalation of conflict between the BCTF and the government via BCPSEA. Perhaps it’s time to consider dismantling BCPSEA and, instead, bringing its operations directly into the Ministry of Education. This would signal that government is willing to start afresh to try and build a new relationship with teachers. After all, it’s the government, not BCPSEA, that holds the purse strings.

We could have engaged in a discussion about the role of school boards in our public education system. Thomas Fleming, in his aforementioned book, noted:

“A history of extremely low voter turnout in school board elections, along with the influence of teacher associations over electoral candidates, has raised serious questions about whether boards in fact actually reflect the public’s educational will or simply serve as a platform for the expression of various special interests — all insistent on greater school spending, regardless of other legitimate public demands government is obligated to consider.”

That quote comes from page 109.

He further points out that only between 5 percent and 10 percent of eligible voters turn up at a school board election not occurring at the same time as municipal elections. In addition, he detailed a by-election in the capital regional district that brought out around only 2 percent of the electorate.

The mandate of school boards has changed over the last century. In the early 20th century local school boards were tasked with hiring the teacher for their often one-room schoolhouse in rural areas, for example, and ensuring that the school was kept up. Provincial inspectors toured the province to make sure that centrally determined educational standards were maintained.

In an extremely influential report authored by Max Cameron in 1946, sweeping changes were proposed to the previously existing model of public school governance. Increased financial efficiency and equitable educational opportunities for all rural and urban British Columbian students required a new approach.

In 1944 there were 650 school districts governed by 437 school boards. Just three years later only 89 school districts remained, and by 1971 this was down to 74. Today there are 60 school districts. Is that the right number? Should their mandate be changed? These are questions the public should have had a chance to discuss and become engaged on discussing prior to the introduction of Bill 11.

We could have engaged in a discussion about whether British Columbians want to follow the New Zealand model, where school boards were eliminated in their entirety, or the Finnish model, where school districts are aligned more closely and intimately with local municipalities for funding, or some other variant.

We could have engaged in a discussion about teacher shortages that will emerge in a few years as projected enrolment increases. All school-aged demographics are expected to rise for at least the next decade. This further suggests that while we may have an excess of teachers being trained today, in three or four years, as the teacher demographic ages and as the number of school-aged children starts to increase, we will almost certainly have teacher shortages, particularly in the areas of French immersion, mathematics and science, where demand exceeds supply even presently.

Rather than perpetuate the boom-and-bust cycle of teacher training and hiring and rather than keeping people for many years on the teacher-on-call list, perhaps a more gradual transition to full-time employment could have been developed. Perhaps we could be discussing this as many of the things in our education system that we could and should have been discussing prior to the introduction of Bill 11.

For example, teacher burnout early on in one’s career is not uncommon. We all know an example of a teacher or two who taught for a few years and moved on, as the requirements placed upon them are simply unbearable, given the support that is lacking at their early age of entry into the teaching profession.

A young teacher might be thrown into a new situation, with multiple class preparations for a range of students with a diversity of skills and backgrounds, with no past teaching material practices to draw upon. New teachers can quickly become overwhelmed with workload. Senior teachers, on the other hand, approaching retirement have a wealth of experience, curriculum resources and best practices. Perhaps it’s possible to negotiate a buddy system, where a retiring teacher signs an agreement to retire gradually over, say, a three-year period, and during that time the starting teacher is paired with the retiring teacher. While the senior teacher gently eases into retirement, the new teacher gently eases into full-time teaching, and the decades of experiences and best practices are passed along from the senior to the junior teacher.

Finally, perhaps we could have started a discussion about innovative ways that would allow school districts to build upon best practices of shared services prior to the introduction of this bill that we are discussing today. Perhaps the government could play a role here and provide the province with a centralized payroll system or legal services, for example. Does each district need to have its own payroll department? Should teachers be employed by the Ministry of Education instead of the board? Are there opportunities for economies of scale?

Bill 11 enables the minister to step in, but again, it would have been preferable to open the bill up first for public and stakeholder input prior to tabling it in this House.

Now, those ideas that I’ve put forward are not any ones that I’m advocating for particularly, or any at all. I’m simply introducing them and putting out these ideas in the hope that they provoke a discussion, a discussion about how public education should evolve in British Columbia. Unfortunately, the approach to educational policy change in the province of British Columbia is viewed by many — by parents, by teachers, by others — in the province as heavy-handed and top down.

Building a social licence for change requires uncomfortable topics to be discussed and new ideas also to be discussed. Sadly, rather than introducing this legislation after such discussions were conducted and concluded, the legislation was brought forward prematurely, and in doing so government sends the wrong message to teachers.

It sends a message that suggests the heavy handed, top-down, rather than collaborative, approach to educational reform is the direction this government is heading.

But please let me reiterate. The status quo between the government and the BCTF cannot continue. The politicization of our public education system serves no constructive purpose. We have outstanding and dedicated teachers in the province of British Columbia. We have a very educated workforce, and we can use it to attract business to our province, as we offer something no one else in the world has — bountiful natural resources and the most beautiful place on earth as our backyard.

Now, the politicization of our public education system is not just the fault of the government. When the BCTF invites the leader of the B.C. NDP to address the 2015 AGM in a partisan speech that ends with him calling on everyone to defeat the B.C. Liberals, which he referred to as “those buggers,” this does nothing to build bridges between teachers and government. It does nothing to build trust in the province of British Columbia. Rather, it further deepens the partisan divide, and everybody loses when that happens. Our children lose, their teachers lose and the parents of those children also lose when public education in the province of British Columbia becomes partisan.

Let’s step back. Let’s let this bill die on the order paper and reintroduce it next year, once a more thorough consultation process has occurred. Let’s get it right, so that we can start rebuilding trust between teachers and government in British Columbia.

NEB Denies My Motion for More Adequate Answers

For more than a year now, I have been trying to get Trans Mountain to answer my questions on their pipeline proposal. As an intervenor in the National Energy Board (NEB) hearings, getting answers to questions is an essential prerequisite to offering an informed argument on whether the pipeline should be built or not.

Sadly, today I learned that the NEB has fully denied my second and final opportunity to get answers to essential questions. What is even more troubling is that I’m not alone.

Collectively, intervenors challenged 1,291 of the roughly 5,700 questions posed to Trans Mountain during the second round of information requests. Of those 1,291 questions, the National Energy Board only ruled in intervenors’ favour 32 times. Put another way, the NEB ruled in Trans Mountain’s favour 97.6% of the time.

Personally, I submitted nearly 100 questions this round and challenged 24 of the answers I received.

To be clear, I was not challenging unsatisfactory answers, or answers I disagreed with. There were many cases where I disagreed with the response that was given, but still received an answer.

Instead, I was challenging answers that simply did not respond to my questions.

Here’s an example:

One of my biggest concerns is that, from the information I have seen, we currently have no capacity to recover sunken or submerged oil. That means that if an oil spill were to occur, and the oil were to sink, we would have no way to clean it up.

For me, this is the line in the sand. We should not be transporting heavy oils along our coast if we cannot clean them up when they sink.

I therefore asked Trans Mountain to provide a list of all equipment owned and operated by Western Canada Marine Response Corporation (WCMRC – the organization that is contracted to respond to oil spills along the B.C. coast) that can be used to recover sunken oil.

In response, Trans Mountain acknowledged that heavy oils can sink under certain circumstances, but failed to provide the requested list. I noted this when I challenged the response, and asked that Trans Mountain provide the requested list. Once again, they did not.

After a back-and-forth, the NEB then gave the following ruling:

Deny – Motion sought information that Trans Mountain is not responsible for, or which is the responsibility of another body (e.g., regulator, tanker operators).

Deny – Motion sought information that may touch upon the List of Issues, but would not contribute to the record in any substantive way and, therefore, would not be material to the Board’s assessment. In some instances, the request was unreasonable or overly broad in scope.

How the NEB can feel that a basic question about WCMRC’s capacity to respond to sunken oil “would not contribute to the record in any substantive way” is beyond me. In my mind, that is one of the most fundamental questions to the whole hearing process. Can we clean up a heavy oil spill? And if we don’t know what equipment WCMRC has, how can we know if we can clean up a spill?

But here’s the other problem:

The NEB has ruled that Trans Mountain isn’t responsible for providing information on behalf of WCMRC. Yet, WCMRC isn’t directly involved in the hearing process. So we have a situation where we cannot get the information on record from Trans Mountain, but we also cannot get the information on record from WCMRC within the formal hearing process.[1]

This brings me back to the essential question: How can the NEB truly evaluate Trans Mountain’s ability to respond to a spill when they seem to have created a situation that denies the Board, and intervenors, the ability to get the information we need?

[1] It should be noted that WCMRC did take the time to meet with my staff and were incredibly helpful. They spent several hours going through their oil spill response plan and answering our questions. However, since that meeting occurred outside the parameters of the hearing process, the information they provided is not necessarily on record within the formal hearings and therefore cannot be considered by the National Energy Board.