Uncategorized

A Tale of Two Cities – Halifax and Victoria

This post was written by my father, John Weaver, and originally published on March 22, 2016 on his blog: beorminga.wordpress.com. I am preserving them on my website as his blog posts are remarkable in their thoroughness and depth of research. Enjoy!

A Tale of Two Cities – Halifax and Victoria

Background

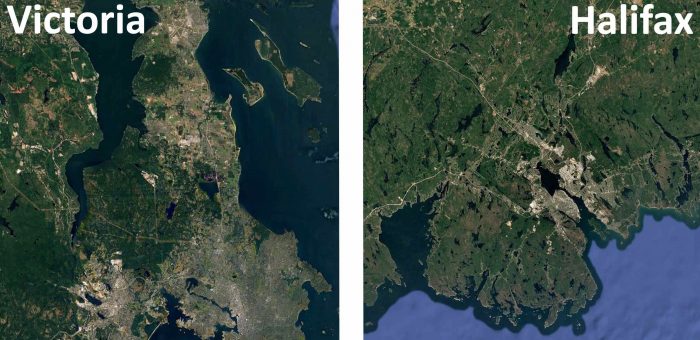

Halifax Regional Municipality and Greater Victoria have much in common. They are both provincial capital cities, they are of similar size (Halifax 414,000, Victoria 359,000 according to official Statistics Canada estimates1 in 2014), they are respectively the home ports of the Royal Canadian Navy’s Atlantic and Pacific fleets, within their regions they are relatively old cities founded by the British (Halifax in 1749, Victoria in 1843), and they both include suburban and rural communities in addition to their urban cores.

But there are significant differences as well. Halifax is not only the capital of Nova Scotia and the largest city in the province but is also the leading commercial centre and transportation hub for the maritime provinces. Victoria, on the other hand, is overshadowed by its younger but very much larger neighbour Vancouver which is not only the dominant city in British Columbia and the third largest metropolitan area in Canada but is also the location of the largest port and the second busiest airport in the entire country.

An even more striking difference between Halifax and Victoria, however, is how the two regional cities are governed. Greater Victoria comprises 13 separate municipalities each with their own mayors and councils (91 of them!), and 3 electoral areas, all overseen by a Capital Regional District (CRD) with limited authority and responsibilities, and whose Board members are appointed or elected by the various municipalities and districts themselves. The Halifax Regional Municipality is a single entity having been created in 1996 through an amalgamation of Halifax City, Dartmouth, Bedford and the County of Halifax. It is governed by the Halifax Regional Council (HRC) of 16 councillors and an elected mayor. Local matters are considered by three community councils, composed of several councillors from the HRC, which make recommendations to the Regional Council. This is the exact opposite of the situation in Victoria where it is the CRD that is subservient to the individual councils rather than the other way round. Board members of the CRD are accountable not to the region but to their municipalities and can, through their councils, block any recommendation from the CRD that would benefit the region as a whole but which they perceive as unfavourable to their own small municipality (and their own prospect of re-election!).

Whereas the Government of Nova Scotia, concerned that the disunity of its largest metropolitan area was hindering its economic development, decided to commission a study of governance in the Halifax region and subsequently introduced an Act to Incorporate in 1995, the present Government of British Columbia prefers a “hands-off” approach to municipal affairs and anyway appears to be totally disinterested in Victoria as it focusses almost exclusively on Vancouver where its support is based.

Andrew Sancton, a well-known expert on municipal amalgamations, states that the Halifax Act was largely the pet project of the Liberal Premier, John Savage, who as mayor of Dartmouth had, ironically, previously opposed amalgamation when it was first mooted by the former Progressive Conservative Premier Donald Cameron. His motives apparently were to reduce public spending and foster economic development, but Sancton claims there was little public interest in the matter and certainly no pressure from external sources for him to pursue this course of action, or in Sancton’s own words2:

“It is extremely difficult to argue that there were strong societal forces urging Canadian provincial governments in the 1990s to implement sweeping municipal amalgamations in major metropolitan areas. In Halifax, the Royal Commission on Education, Public Services, and Provincial-Municipal Relations called for a single municipality as early as 1974. In 1992 the provincially appointed Task Force on Local Government arrived at a similar conclusion. In neither of these cases was there great public interest in the issue. … Such policies were brought in with little or no thought by provincial premiers who acted as they did in response to the particular political circumstances in which they found themselves. They made little or no effort to mobilize consent for these policies beyond a small group of cabinet ministers who in turn helped control obedient caucuses.”

Circumstances in Victoria couldn’t be more different. The amalgamation question has been alive and debated for decades: numerous public discussions have taken place; several well-attended forums featuring panels of experts and distinguished guest speakers have been organized; citizens’ groups seeking an independent study of local governance have been formed (Amalgamation Yes, Grumpy Taxpayer$ of Greater Victoria, Greatest Greater Victoria Conversation); countless articles and letters on the topic have been published in the local press3; radio and TV interviews on amalgamation are a regular occurrence; and so on. In 2014 an Angus Reid poll determined that 84% of residents in the Capital Region favoured some sort of amalgamation with 50% “strongly in favour”. An overwhelming majority of 89% supported a non-binding referendum on the issue, and 80% expressed support for an independent study and cost-benefit analysis of amalgamation in the region, extraordinarily high figures for a poll of this nature.

Local councils and mayors have traditionally been opposed to any change in the present governmental structure which is not surprising since many of them would be losing their positions in a unified region. Possibly influenced by the poll results, however, and reacting to pressure from various business, professional and citizens’ organizations, eight of the thirteen municipalities agreed to put some sort of question on the ballot when the municipal elections were held in November, 2014, asking if voters favoured a non-binding, independent review of governance in the region. It was perhaps a reflection of the disunity in the region that there was no agreement on a simple, common question; rather each municipality phrased the question to suit their own purposes – one was so convoluted that the result could be open to various interpretations, another was worded virtually to invite a ‘No’ vote. Five municipalities (fairly small ones) deemed the topic of no interest to their residents and declined to place any question on the ballot. Despite this lack of enthusiasm by local politicians, the public responded with a higher than average turnout in those municipalities with a question on the ballot and a resounding 75% vote in favour of a review of local governance.

It is tempting to ask if Professor Sancton would regard the case for amalgamation in Greater Victoria different from and more compelling than that in Halifax given that it has grown out of a grassroots campaign rather than a top-down imposition by the provincial government.

Financial Considerations

The first thing opponents of the Halifax amalgamation will point out is that the promised savings were never realized in the short term. They will mention the fact that salaries rose to the level of the best paid equivalent positions among the pre-amalgamation municipalities and that economies of scale were a dream never realized. According to Robert Bish4 the cost of implementing the amalgamation alone was four times the original estimate and he further stated that:

“It is not yet apparent that any cost savings will result. From 1996 to 2000, user charges increased significantly and average residential property taxes rose by about 10% in urban areas and by as much as 30% in suburban and rural areas.”

All that was some time ago, of course, and although proponents of amalgamation are primarily interested in delivering a more efficient, more equitable and less complicated model of governance rather than in any potential cost savings that may result, it is nevertheless interesting to compare the current costs of government in the two regions, Halifax and Victoria, and their economic development. The Executive Summary in Halifax’s proposed operating budget5 for 2015/16 begins with the statement:

“As a municipality, Halifax is in a strong, healthy financial position. The long term financial position of the municipality is generally sustainable as evidenced by its debt position. In line with the long-term trend, the Tax Supported Debt of the Municipality continues to steadily decline. Debt had peaked in 1998-99 at nearly $350m but at the end of 2015-16 is expected to total $256.3m, a decline of nearly $100m, more than 25%. This has been achieved despite a substantial increase in the population and higher demands for capital expenditures.”

On this same theme, Halifax Councillor, Reg Rankin, was quoted in the February 4th, 2016, issue of ‘The Coast’, a Halifax newspaper, as stating

“Today, this is the equivalent of paying off two-thirds of our mortgage. We’re so pleased it has been accomplished over a generation, a generation I guess since amalgamation.”

Whatever Professor Bish’s post-amalgamation prognosis in 2001 might have been, it is apparent that in 2016 the Halifax Regional Municipality is in a strong and still-improving financial position.

Further evidence6 of its economic health is provided by its admirable economic development since 2005 when it was placed 15th out of Canada’s 28 large city regions in terms of GDP growth. It rose to 8th place in 2014 and is predicted to be 1st in 2015, while over the same period Greater Victoria has fallen from 4th to 27th position in the same table. One cannot simply attribute Halifax’s remarkable economic growth to amalgamation, of course, but it certainly hasn’t hampered it! Meanwhile the Greater Victoria Development Agency has recently identified the lack of collaboration and common goals among the region’s multiple jurisdictions as a major reason for its sluggish performance and lack of success in attracting available funding. It proposed formation of a South Vancouver Island Development Association, funded by all constituent municipalities, to rectify the situation. The proposal had to be ratified (or not!) by all 13 councils, of course, an obstacle and delay that would have been entirely unnecessary if Greater Victoria were a unified city-region. In the end 11 municipalities and the Songhees First Nation signed the agreement with only two small semi-rural municipalities, Metchosin and Sooke, opting out.

A detailed comparison of revenues and expenditures in the two metropolitan areas is not a simple task that requires little more than a straightforward perusal of their operating budgets. The figures for Halifax are readily extracted from the published Consolidated Financial Statements for the Regional Municipality that are available on the internet7, but the corresponding amounts for Greater Victoria are spread over 14 different financial statements which are not fully consistent in the way the data are presented. A further complication arises because Halifax shows totals for the fiscal year ending on 31st March while the Greater Victoria municipalities use the calendar year for their financial statements.

There is also the “apples and pears” problem of trying to ensure that comparisons are like with like, since some services listed as part of the operating budget in one region may be treated differently in the other. One obvious example is the cost of transit. Halifax Regional Transit is a responsibility of the municipality whereas the Victoria Regional Transit Commission is a branch of BC Transit, which is partially financed by the Provincial Government. In 2014-15, for example, the total cost of operating transit in Victoria was $120.5 million to which local municipalities contributed only $28.8 million from their property taxes8. In the same fiscal year, expenditure for Halifax Transit was $110.9 million with property tax revenues contributing $76.3 million9, a far higher proportion than in Victoria. The three school districts in the Capital Region receive funding from the Ministry of Education which in turn receives municipal taxes collected on its behalf by the constituent municipalities themselves. The financial statement for Halifax clearly defines a single line item for ‘Educational Services’ but it is not at all clear in Greater Victoria what proportion of the Ministry’s grants to the school districts are funded by the various amounts collected by the municipalities. ‘Amortization’ is another significant entry on all the financial statements; these recorded amounts will depend on a number of factors that require detailed examination beyond my expertise.

There may be other examples of inappropriate comparisons that I am not aware of and, in any case, the different conditions existing in two separate provinces make meaningful interpretations of results somewhat tricky at best. Harsher winters in Nova Scotia, for example, mean heavier road maintenance and snow removal costs, and the sheer size of Halifax Regional Municipality is a factor not reflected in population figures alone. It covers a huge land area of 5490 km2 which is nine times larger than the area of Greater Victoria (696 km2) and even over twice that of the entire CRD (2341 km2) which includes the largely undeveloped and sparsely populated Juan de Fuca Electoral Area. Halifax region hugs the coast for a linear distance of roughly 150 km and extends about 50 km inland. The CRD would have to expand as far as Nanaimo in order to encompass a comparable area. No-one on Southern Vancouver Island is advocating an amalgamation on that scale.

Thus it soon became apparent that an unravelling of all the intricacies of these revenues and expenditures were best left to a qualified financial auditor. Two parts of the financial statements, however, which can be retrieved relatively unambiguously, appear to lend themselves to a direct comparison. They are wages and salaries, and protective services. It is also a fairly simple exercise to compare the grand totals of revenues and expenses (slightly modified to account for differences arising from some incompatible ways of reporting revenues and expenses in the two regions). The financial statements in these three areas are compared in the following paragraphs.

Wages and salaries. Wages and salaries, including benefits, are stated in the first line of expenses in the Table of Segmented Information included in one of the ‘Notes to Financial Statements’ in the audited Consolidated Financial Statements for each municipality. They are shown here in Table 1 which suggests that Greater Victoria residents pay about $100 more per person for the salary and wages of mayors, councillors and municipal staff than the residents of Halifax Regional Municipality. With 13 councils plus the CRD all employing their own administrative officers and staff this is perhaps hardly surprising. Halifax’s one mayor receives a salary of $168,449 while the 13 mayors of Greater Victoria are paid a combined total of roughly $450,000. All available evidence suggests that the cost of wages and salaries would be reduced in an amalgamated region.

Table 1

Expenditures on Salaries and Wages

(Figures in millions of dollars except last column);

| Municipality | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | Average | Per Capita |

| Halifax | 324.0 | 343.5 | 333.8 | $806 |

| 2013 | 2014 | |||

| CRD | 49.5 | 51.8 | ||

| Victoria | 104.1 | 107.3 | ||

| Saanich | 87.9 | 90.7 | ||

| Esquimalt | 12.9 | 13.5 | ||

| Oak Bay | 19.8 | 19.6 | ||

| Central Saanich | 10.5 | 11.0 | ||

| North Saanich | 5.2 | 5.4 | ||

| Sidney | 6.6 | 6.8 | ||

| View Royal | 4.1 | 4.3 | ||

| Colwood | 6.7 | 7.0 | ||

| Langford | 8.1 | 9.3 | ||

| Metchosin | 1.0 | 1.1 | ||

| Highlands | 0.6 | 0.6 | ||

| Sooke | 3.0 | 3.1 | ||

| Total Victoria | 320.0 | 331.5 | 325.8 | $908 |

Protective services. The police, fire and emergency preparedness services provided for citizens in all municipalities across Canada must be fairly standard. Thus one would expect the cost per person for such services to be fairly uniform in communities of similar size. “Protection services” is also a separate category of revenues and expenses on financial statements so a direct comparison between regions of similar size is fairly straightforward. There are, of course, significant differences between Greater Victoria and Halifax in how the delivery of such services is organized. The Fire and Emergency Services Organization Chart for Halifax shows one Fire Chief supported by a Deputy Chief of Operations, a Deputy Chief of Operations Support, and a Manager of the Emergency Management Office. Every municipality in Greater Victoria has its own Fire Chief and fire department, some of which are run on a volunteer basis, as are some of the rural components of the Halifax Regional Fire Department. The three former police forces in Halifax, Dartmouth and Bedford have been amalgamated into one Halifax Regional Police department responsible for policing those three former municipalities along with some neighbouring districts. Policing in the rural areas is contracted out to the RCMP. Greater Victoria, by contrast, maintains four separate departments in Victoria/Esquimalt, Saanich, Oak Bay and Central Saanich each with their own Police Chiefs and with markedly different caseloads per officer.

Two RCMP detachments, one based in Langford and the other in Sidney, serve the Westshore and north Peninsula respectively. Small detachments are also present on Salt Spring and Pender islands which fall within the jurisdiction of the CRD. The Senior Manager of the CRD’s protective services is also the Emergency Manager for the entire region.Table 2 shows compares the cost of protective services in the two regions. The per capita expense in Greater Victoria is slightly greater ($20) than in the Halifax Regional Municipality.

(Figures in millions of dollars except last column)

| Municipality | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | Average | Per Capita |

| Halifax | 192.1 | 203.0 | 197.6 | $477 |

| 2013 | 2014 | |||

| CRD | 8.5 | 8.7 | ||

| Victoria | 64.2 | 65.9 | ||

| Saanich | 47.2 | 50.3 | ||

| Esquimalt | 11.3 | 11.9 | ||

| Oak Bay | 8.9 | 8.6 | ||

| Central Saanich | 6.9 | 7.3 | ||

| North Saanich | 2.7 | 2.8 | ||

| Sidney | 4.0 | 4.1 | ||

| View Royal | 3.0 | 3.1 | ||

| Colwood | 5.2 | 5.5 | ||

| Langford | 8.6 | 10.1 | ||

| Metchosin | 0.7 | 0.7 | ||

| Highlands | 0.4 | 0.4 | ||

| Sooke | 3.0 | 3.2 | ||

| Total Victoria | 174.6 | 182.6 | 178.6 | $497 |

Total revenues and expenditures. The grand totals of revenues and expenditures in each jurisdiction are prominently displayed on all financial reports. While the figures themselves provide a simple overview of how much tax and other revenue is generated in the two regions and what their overall operating costs are, they are not directly comparable in a meaningful way because of the “apples and pears” reasons given earlier. Their interpretation is further complicated by the different formats used in reporting year-end financial statements in different municipalities. For example, Sooke clearly identifies taxes received as “Net taxes available for municipal purposes” and in an explanatory note lists the actual property taxes collected less taxes levied on behalf of schools, CRD, hospitals, Municipal Finance Authority, BC Assessment and BC Transit. North Saanich and Sidney also state that taxes shown under revenues are for municipal purposes, but others simply state “Taxes”. I have assumed these are all net taxes since there are no payments to the various outside agencies listed under expenses and proportionally the amounts seem consistent with those for municipalities reporting net taxes. Payments to the CRD are included under revenues in the CRD’s Financial Statement of course. Halifax also collects taxes for its school system but records the amount as a separate item in Revenue under Educational Services. The identical amount is then shown under Expenses as a lump sum payment to Educational Services. The funds simply flow through the Financial Statement without having any effect on the overall surplus or deficit. In Greater Victoria such payments to outside agencies do not appear at all. Thus for a fair comparison the amounts appearing under Educational Services have been omitted from the totals for Halifax in Tables 3 and 4 which show the total revenues and expenses for Halifax alongside the corresponding totals for the combined Capital Region. (An even fairer comparison would have resulted if the taxes for transit in Halifax and its net operational expenses had also been removed from the totals because transit in Greater Victoria is run by BC Transit, not by the CRD or individual municipalities.) Note that the total of expenses in the tables is not a measure of property taxes levied in the two regions. It excludes all the taxes collected on behalf of other agencies in Greater Victoria and those for educational services in Halifax.

Table 3

Revenues

(Figures in millions of dollars except last column)

| Municipality | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | Average | Per Capita |

| Halifax | 778.9 | 815.0 | 797.0 | $1925 |

| 2013 | 2014 | |||

| CRD | 181.8 | 191.6 | ||

| Victoria | 209.5 | 221.2 | ||

| Saanich | 189.1 | 187.5 | ||

| Esquimalt | 31.1 | 33.3 | ||

| Oak Bay | 34.0 | 36.7 | ||

| Central Saanich | 25.1 | 25.2 | ||

| North Saanich | 17.5 | 17.9 | ||

| Sidney | 18.8 | 20.1 | ||

| View Royal | 18.0 | 12.5 | ||

| Colwood | 19.7 | 19.4 | ||

| Langford | 55.1 | 51.1 | ||

| Metchosin | 5.3 | 4.8 | ||

| Highlands | 3.8 | 2.6 | ||

| Sooke | 13.6 | 16.2 | ||

| Total Victoria | 822.4 | 840.1 | 831.3 | $2316 |

Table 4

Expenses

(Figures in millions of dollars except last column)

| Municipality | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | Average | Per Capita |

| Halifax | 733.0 | 779.1 | 756.1 | $1826 |

| 2013 | 2014 | |||

| CRD | 147.6 | 148.7 | ||

| Victoria | 173.9 | 174.0 | ||

| Saanich | 151.1 | 164.4 | ||

| Esquimalt | 29.5 | 30.2 | ||

| Oak Bay | 32.2 | 32.5 | ||

| Central Saanich | 25.8 | 25.2 | ||

| North Saanich | 15.1 | 15.9 | ||

| Sidney | 17.9 | 17.9 | ||

| View Royal | 12.1 | 12.4 | ||

| Colwood | 17.7 | 18.5 | ||

| Langford | 53.0 | 39.3 | ||

| Metchosin | 4.4 | 4.6 | ||

| Highlands | 2.7 | 2.8 | ||

| Sooke | 11.6 | 12.0 | ||

| Total Victoria | 694.6 | 698.4 | 696.5 | $1940 |

What can we conclude from this discussion? First, I think one can immediately put to bed the alarmist claims by some politicians that amalgamation would dramatically increase the costs of local government in the Victoria region. The tabulated data, unprofessional as they are, indicate that after amalgamation Halifax has possibly lower rather than higher operating costs per person than the combined costs of the Capital Region’s 13 separate municipalities. Indeed, they suggest that in certain areas there are probably modest savings to be gained through amalgamation of a mid-size city-region with a population of about 400,000.

Other Factors

Potential fiscal savings are not the main reason proponents support amalgamation, however, a point that defenders of the status quo seldom recognize. There are more compelling grounds of a wider nature admirably summarized by Rudiger Ahrend et al.10 who state in their abstract: “A city’s metropolitan governance structure has a critical influence on the quality of life and economic outcomes of its inhabitants.” … “Administrative fragmentation, which complicates policy coordination across a city, has a negative effect on individual productivity. This finding, combined with benefits from good governance such as improved transport and lower pollution levels, highlights the importance of well-designed metropolitan authorities.” Referring to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the authors go on to say: “The OECD Metropolitan database defines ‘functional urban areas’ across the OECD on the basis of a common method that relies on settlement patterns and commuting flows rather than administrative borders.” … “A large number of municipalities in metropolitan areas can complicate policy coordination among local governments. A potential solution to this coordination problem could be the amalgamation of municipalities within a metropolitan area. ”On this definition Greater Victoria is certainly a single functional urban area as anyone who uses the Trans-Canada or Pat Bay highways at commuting time knows. So how do Halifax and Greater Victoria compare when measured against those factors related to economic well-being and quality of life referred to by Rudiger Ahrend et al.? Of course, with its scenic setting, mild climate and general ambience Victoria has a natural built-in advantage with regard to quality of life, and it is fortunate to have a well-educated population including some, especially among those who have retired to the region, who are quite wealthy and willing to support arts and culture. But there are other factors which should contribute to the economic success and efficiency in the two regions which are discussed below.

Policing. With an amalgamated regional police force and one emergency call centre for its core districts it is inconceivable that Halifax could experience the shocking delay in responding to a frantic 911 call that occurred in Oak Bay some years ago. The address was on the artificial border between Victoria and Oak Bay and the resulting confusion eventually involved three different police forces. Six hours later police discovered five bodies inside the house in a murder-suicide crime. This was a terrible failure due to lack of communication between separate police forces. Attempts to create integrated units for Greater Victoria have only had limited success with municipalities joining and subsequently withdrawing because of costs. Kash Heed, a former BC solicitor general (and a former police chief in West Vancouver) is quoted as saying integration is a failed policy that fuels conflict rather than co-operation and that integration is a “band aid solution to a gaping wound”. Another problem is the enormous difference in cost per capita among the municipal police departments within Greater Victoria, $455 for Victoria, $263 for Saanich, $257 for Oak Bay and $245 for Central Saanich in 2013. This is because VicPD is responsible for policing the downtown core where much of the crime, drug-dealing and homelessness exists. Ironically over 50% of downtown crime is committed by residents of other municipalities in the region. Halifax is well ahead of Greater Victoria in policing.

Influence in Ottawa. Halifax is a member of the 21-strong Caucus of Big City Mayors which meets two or three times a year, sometimes with leaders of government, business, labour and the economy, to plan strategies for dealing with infrastructure renewal, homelessness, social housing, sustainability, and related issues. Their most recent meeting in early 2016 was with Justin Trudeau, the newly-elected Prime Minister. With a population of only 80,000 Victoria doesn’t qualify for membership of the Caucus but it is certainly burdened with the “big city” issues listed above. It is frustrating to see smaller (but unified) cities such as Regina, Saskatoon, St. John’s, Windsor, Gatineau, Kitchener, all having the ear of the Prime Minister while Victoria is excluded simply because it is a constricted urban core surrounded by other independent suburban municipalities. Unfortunately, unless the region is represented by a single mayor it will be forever excluded from this influential body. Halifax is poised to take advantage of funding made available to big cities while Victoria, Saanich, Langford etc. will compete with each other for the scraps left over.

Payments in lieu of taxes. Both Halifax and Greater Victoria receive substantial payments in lieu of taxes from the Federal Government for the Atlantic and Pacific Naval Bases and Dockyards respectively. The difference is that while the funds going to Halifax benefit the whole region, in Greater Victoria it is the municipality of Esquimalt (population 16,800) that receives the entire payment representing over 40% of its tax revenue, even though many of the naval and dockyard personnel reside in other municipalities. The general taxpayer in Halifax gets the fairer deal.

Sewage treatment. Although scientific and medical opinion is firmly of the view that secondary sewage treatment in Victoria is unnecessary and a complete waste of money, the fact remains that it has been mandated by the Provincial Government. The CRD took charge of the project and the history of the sorry saga that followed exemplifies all that is wrong with that body and with governance of the Capital Region. After ten years of debate, planning, public consultation and engineering reports, and an expenditure of nearly $100 million there is still no site selected for the treatment plant(s) or a decision on whether there will be one, two or more plants. The estimate of the overall cost now exceeds $1 billion. At one time a site had been selected but Esquimalt council refused to rezone the additional land needed to accommodate the plant. One small municipality’s action caused the collapse of the entire project. In Halifax, where treatment is most definitely needed (its effluent empties into the enclosed, sheltered waters of Halifax harbour) construction of treatment plants didn’t begin until after amalgamation because as separate cities, Halifax and Dartmouth could not reach agreement on the design of the plants. Sewage treatment was completed in 2011 at less than a third of the estimated cost for Victoria. And the moral of the story? It took amalgamation to get things done.

Arts and recreation. Victoria had the foresight and good fortune to retain and restore two lovely Edwardian theatres, the 1416-seat Royal, home to Pacific Opera Victoria and the Victoria Symphony, and the 772-seat McPherson Playhouse used for plays, concerts and amateur productions. Although they serve regional audiences and beyond, Victoria is the sole municipal contributor to the McPherson and only three municipalities (Victoria, Saanich and Oak Bay) contribute to the Royal Theatre. (Professional theatre is also staged at the Belfry Theatre, a converted church building, and the Roxy Theatre, while the 800-seat Alix Goolden Hall and the 1228-seat University of Victoria Auditorium are alternative venues for musical concerts.These are independently run facilities, however.) Despite this rich choice of venues for Victoria’s vibrant cultural scene, what is lacking for a capital city is a modern performing arts centre with a large stage suitable for ballet and major touring productions, and acoustics that befit a fine symphony orchestra. Given the reluctance of other municipalities to provide funds for theatres located in downtown Victoria, it is not surprising that after decades of informal campaigns, studies and proposals there is no sign of any progress having been made towards building such a facility. By contrast, Halifax is not nearly as well provided with performance spaces. Its main professional theatre is the Neptune which seats 479 playgoers. For larger productions and symphony concerts it uses the 1023-seat Rebecca Cohn Auditorium on the Dalhousie University campus. These are meagre facilities compared with Victoria, but the Halifax Regional Council does have a new performing arts centre officially on its agenda as one of the large projects in the concept phase. With the council representing the whole of the region it is likely to be built while unofficial groups in Greater Victoria are still talking. The same can be said for arenas. Many of the municipalities in Greater Victoria have built their own community recreational centres which is excellent, but a city-region of 360,000 also needs a large arena suitable for a semi-professional hockey team, figure-skating and gymnastics competitions, trade shows and rock concerts. Victoria’s tired old 4200-seat Memorial Arena was replaced in 2005 by a new 7000-seater courtesy of the City’s taxpayers alone. Halifax has an arena with seating for 10,600 spectators (12,000 for concerts) but is already considering building a bigger one with a capacity of over 15,000 spectators for hockey games. If this comes to fruition the costs will be distributed equitably across the region. One can only imagine what kind of arena Victoria could have had if it had been an amalgamated city when the aging Memorial Arena was replaced.

Garbage collection. Each municipality in Greater Victoria has its own regulations and methods for garbage pick-up. Whereas Victoria employs several men and one truck for residential services, Saanich, with a more automated system, needs only one man and a truck. Langford doesn’t provide any garbage collection at all as a municipal service − residents have to make their own arrangements with a private company. Some municipalities provide residents with two standard containers, one for general non-recyclable rubbish and the other for organic kitchen waste, others do not. Halifax has a uniform method of garbage collection but it appears to be less advanced than some of those in Greater Victoria.

Neighbourhood representation. Halifax is divided into 16 Districts each electing one councillor. The Districts are grouped into 3 Community Councils comprising the councillors elected in each District. The Community Councils make recommendations to the Regional Council which has final authority. Local public input and consultation is generally made at the Community Council level or, personally, to the District councillor. In Victoria and Saanich, members of neighbourhood associations are ordinary residents interested in community activities, planning, development, and the general character of the areas in which they live. Board members of a neighbourhood association, who meet usually once a month, are all volunteers. Each councillor is assigned to one or more neighbourhoods and attends their board meetings if possible. The associations may draw up neighbourhood plans, advise on land-use management and raise objections to unwanted developments, but they have no final authority which rests with the municipality. It would be possible to copy the model of regional governance in Halifax by dividing the CRD into perhaps four community councils, say (i) East Victoria, Oak Bay, Gordon Head and Cadboro Bay, (ii) West Victoria, Esquimalt, View Royal and South Saanich, (iii) West Shore and Juan de Fuca, and (iv) Cordova Bay, Prospect Lake, Peninsula and Islands, with each “Community” sub-divided into three or four “Districts”. Some members of the neighbourhood associations are ambivalent about amalgamation as they feel it would relegate them to an even more remote position of influence from the ultimate decision-makers, but perhaps they could play a similar role in their District if the Halifax model were adopted.

Rural protection. Some opponents of amalgamation claim it would threaten protection of rural areas. Halifax includes a large rural component and it remains intact. Saanich, the largest of the Greater Victoria municipalities has managed to preserve its rural part despite the encroachment of suburban housing. It is the smaller municipalities that are more worrying, as it is harder for them to resist the temptation of increasing their tax base when presented with attractive offers from developers. Langford cleared forested areas, including a Garry Oak meadow, in order to develop its cluster of box stores. Central Saanich, a mainly rural community, has allowed an ugly strip of light industry, warehouses and commercial businesses to grow along Keating Cross Road, and now a new proposal has emerged to build yet another shopping mall on the outskirts of Sidney, the last thing that compact community needs. A single regional plan for the entire region would surely help to prevent such haphazard developments from happening. In my opinion, amalgamation would provide better rather than less preservation of the rural areas in the Capital Region.

Emergency preparedness. Halifax has one emergency plan and one emergency call centre. Victoria, situated in an earthquake zone, has 13 plans and 3 call centres. The mind boggles at the sort of chaos that will develop if the ‘big one’ occurs with the present administrative structure still in place.

Infrastructure renewal, traffic and planning. Two bridge replacements demonstrate the unfair burdens placed on individual municipalities when infrastructure serving the entire region is renewed. The Johnson Street bridge is on one of three routes connecting the West Shore to downtown and beyond. Yet it lies entirely within Victoria which must therefore bear the full cost, even though it is Esquimalt which probably receives the most benefit in this case. Much of the funding for the Craigflower Bridge upgrade came from the gas tax, but Saanich and View Royal, the municipalities at either end of the bridge (just – the Esquimalt border nudges up to the corner of the bridge on the View Royal side), each contributed $2.5 million. Much of the traffic on this bridge, especially at commuting time, is to and from the naval dockyard in Esquimalt, which was not financially involved in this project. Planning in the region is not well coordinated. Langford’s box stores were planned by that city alone, yet they attract traffic from other parts of Greater Victoria causing congestion on the Trans Canada highway and on the road leading from the stores to the highway. Langford is, however, anticipating the possibility of a reopening of the E & N railway for commuter trains between the West Shore and downtown while, ironically, Victoria has severed the rail link into the city centre because it couldn’t afford the additional cost of incorporating it into the new Johnson Street bridge. There appears to be no coordinated plan in Saanich and Central Saanich to identify potential arterial routes through their municipalities to the airport and BC ferry terminal, with the result that all through traffic to those destinations is funnelled onto the already busy Pat Bay highway. And surely it is only in Victoria that one encounters such bizarre situations as a plethora of building codes, designated bicycle lanes ending abruptly when reaching an invisible line between two municipalities, a default speed limit that suddenly changes when driving along what appears to be the same road at a constant speed, a suburban road where one side is like a country lane with no kerb or sidewalk while the other is a typical suburban street, a house that receives two partial tax bills because it happens to straddle two municipalities on an ordinary suburban street. All quite hilarious, but unfortunately true. I know little about Halifax in these departments but I’m sure it has a regional plan, a standard building code, uniform traffic regulations and no invisible boundaries!

Conclusion

Amalgamation of the Halifax municipalities was not perfect. Almost certainly it covered too large an area. With its historical urban core centred on Halifax, Dartmouth and Bedford surrounded by vast tracts of rural land dotted with small communities, it is a marriage of barely compatible parts. In such a large region some rural residents probably feel disconnected from the city and with their different priorities may perhaps disproportionately influence policy issues on such urban issues as libraries and transit. Greater Victoria’s geography is rather different. Only the small municipalities of Sooke, Metchosin and Highlands on its fringes are truly rural (and even they also serve as bedroom communities for daily commuters) while Central and North Saanich and parts of Saanich itself contain pockets of productive and protected farmland. It resembles a more cohesive community containing a mix of countryside, suburbia and urban core which geographically, at least, is probably even more suited to amalgamation than Halifax.Otherwise, however, amalgamation of the Halifax region appears to have been a great success. The amalgamated city is thriving economically, it has reduced its debt in spectacular fashion and it punches well above its weight in national affairs. I believe one would be hard-pressed to find local leaders, businesspeople, members of the arts community and government officials yearning for a return to its previous balkanized structure of governance. Amalgamation has worked well for Halifax. It should be held up as an example that Greater Victoria should emulate.

Amalgamation? YES!

John Weaver

February, 2016

References

1Annual population estimates by census metropolitan areas, July 1, 2014, http://www.statcan.gc.ca/dailyquotidien/150211/t150211a001-eng.htm

2Andrew Sancton: Why Municipal Amalgamations? Halifax, Toronto, Montreal, in “Canada: The State of the Federation 2004, Municipal-Federal-Provincial Relations in Canada” (Robert Young & Christian Leuprecht editors), McGill University Press, 2006, pp 119-134.

3See http://www.amalgamationyes.ca/media–events.html for a selection of such articles and letters.

4Robert L. Bish, Local Government Amalgamations; Discredited 19th-Century Ideals Alive in the 21st Century, C. D. Howe Institute Commentary No: 150, March 2001, pp 35.

5Proposed Operating Budget 2015/16, Section A, Executive Summary, https://www.halifax.ca/budget/documents/proposed_operating_book.pdf

6A New Regional Strategy and Model for Economic Development in South Vancouver Island, 2015 Report published by the Greater Victoria Development Agency Board, pp 46.

7Consolidated Financial Statements, http://www.halifax.ca/finance/

8How Victoria Regional Transit is Funded, http://bctransit.com/*/about/facts/victoria

9Proposed Operating Budget 2015/16, Section I3, Halifax Transit Operating Budget Overview, https://www.halifax.ca/budget/documents/proposed_operating_book.pdf

10Rudiger Ahrend, Alexander C. Lembcke, Abel Schumann, Why metropolitan governance matters a lot more than you think, VOX, CEPR’s Policy Portal (Research based policy analysis and commentary from leading economists), 19 January 2016, pp 6: see http://www.voxeu.org/article/why-metropolitan-governance-matters

11Police resources in British Columbia, 2013, http://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/law-crime-and-justice/criminaljustice/police/publications/statistics/2013-police-resources.pdf

John Trevor Weaver (November 5, 1932 – April 26, 2025)

Obituary

John Weaver passed away peacefully at the age of 92 on Saturday, April 26th, 2025, at the Royal Jubilee Hospital surrounded by his loving family.

He is survived by Ludmilla, his wife of 65 years; his children Andrew (Jordan), Anthony (Laurence) and Alexandra (Dan); grandchildren Maria, David, Hélène, Paul, Nicolas, Nicholas, Charlotte and Georgia. He is also deeply mourned by his sister Margaret, and his extended family and friends in Canada and abroad.

John was born on 5th November 1932, in Birmingham, UK where he spent his childhood and attended Solihull Grammar School. In 1950 he enrolled at Bristol University and earned an Honours degree in Mathematics. He also joined the University Training Corps, and in 1953 was selected as one of two representatives from Bristol University to march in the coronation procession of Queen Elizabeth II. That same year, John boarded the Empress of France in Liverpool and set sail for Montreal on his way to the University of Saskatchewan where he completed both his MSc and PhD in Physics. It was there that he met his future wife Ludmilla at the International Students’ Club. They married in 1960.

After honeymooning in the UK and continental Europe they moved to Victoria where John worked as a research scientist at the Pacific Naval Laboratory in Esquimalt. In 1966 he accepted a faculty position at the University of Victoria and later served as Chair of the Physics and Astronomy Department. John then became the first Dean of UVic’s newly formed Faculty of Science and held this position until his retirement in 1998.

John will be remembered as a true gentleman, devoted husband, father, grandfather, and patriarch. He was kind and highly respected by a large circle of extended family, friends, and colleagues around the world. His strength of character, empathy, kindness, erudition, humour, and unwavering devotion to his family will be sorely missed.

Special thanks to the staff at Royal Jubilee Hospital, especially nurses Rowena, Nathan, Jeremy, Gabriella and Kat for their compassionate and professional attention to his needs. Special thanks also to the staff at Amica Somerset House, especially Jodie and Joy.

A funeral will be held at Christ Church Cathedral in Victoria, BC, on Monday, 5th May, at 1 pm (PST).

Funeral service

Eulogy

When John, Dad, Grandpa or Gramps as David and I know him, was diagnosed with terminal cancer in February, he decided to prepare his own eulogy. As he told his daughter Alexandra, “I want to make sure the dates of the events in my life are mentioned correctly”. This was a perfect example of John’s meticulous attention to detail – a trait we deeply admired, even if it could be a bit frustrating when he corrected our grammar mid-sentence.

When John, Dad, Grandpa or Gramps as David and I know him, was diagnosed with terminal cancer in February, he decided to prepare his own eulogy. As he told his daughter Alexandra, “I want to make sure the dates of the events in my life are mentioned correctly”. This was a perfect example of John’s meticulous attention to detail – a trait we deeply admired, even if it could be a bit frustrating when he corrected our grammar mid-sentence.

He also said that he wanted a eulogy that traced his journey in life, believing that would be more interesting than an “exaggerated account of how wonderful he was”. Sadly, John passed away before he was able to finish it. On the positive side, it leaves us room to finish his story in our words….

John Weaver was born on 5 November, 1932 in Birmingham, UK and grew up in nearby Solihull. The area was a major target for the Luftwaffe in World War 2 and John spent many nights in an air raid shelter in the back garden. In a field opposite the house was a searchlight and an anti-aircraft gun, down the road a barrage balloon and right outside the house a smokescreen incinerator which emitted oily, black smoke to obscure enemy targets on the ground. It is not surprising therefore that several houses on Solihull Road were bombed, but not his fortunately.

John won a place at Solihull School, an independent ‘public’ school which took scholarship boys. After the war, John’s father (who had been employed on war work at the nearby Rover company) obtained a new position as a sales representative for a Birmingham company making hotel bar equipment and was transferred to Bristol. Since John was approaching the all-important School Certificate examination, he stayed on in Solihull, living with his grandparents, while the rest of the family, mother, father and his younger sister Margaret moved to Bristol. This was a decision he later came to regret. On the positive side, one of his school friends invited him to join his family on a holiday in Switzerland. This was a transformative life experience for John who up to this point had been the consummate parochial Englishman, having rarely travelled beyond his local comfort zone, only once to London and never abroad. He was immediately fascinated by the variety of cultures, languages, ways of life, tastier food and superior infrastructure on the continent. He became an instant Europhile, and the experience inspired a love of travel and adventure which lasted throughout his life. Later in life this led him to travel extensively all across the world with Ludmilla and family.

In 1950 he reunited with the family when he enrolled at Bristol University to study for an Honours degree in Mathematics. In the summer vacations he returned to the continent, hitch-hiking around France and Switzerland with friends and working in an aluminium factory in Norway. He also joined the University Training Corps, and in 1953 was selected as one of two representatives from Bristol University to march in the coronation procession of Queen Elizabeth 2nd.

By chance, a distant relative who had married a Professor of History at the University of Saskatchewan, visited the family while on a tour of the UK. She suggested John experience life at a Canadian university by taking a Master’s degree at the University of Saskatchewan. John took this suggestion with a pinch of salt but was very surprised when several weeks later a letter arrived from the Head of the Physics Department inviting him to apply for graduate work with the promise of financial support. The relative had followed through after all but with a slight error — she got the wrong department, Physics rather than Mathematics! But with his recently acquired sense of adventure John thought “Why not?”. In September 1953, much to his sister’s dismay that he was once again leaving the family, John handed in his Ration Book as he boarded the ‘Empress of France’ in Liverpool and set sail for Montreal.

To say that his arrival in Saskatoon, a small town isolated in the middle of the prairies with their fierce winters and hot dry summers was a cultural shock, is an understatement. His home in England was a three-day train journey and a week-long sea voyage away; telephone calls to family were very expensive and had to be booked well in advance for a timed three-minute conversation. Nevertheless, John found the Saskatchewan people warm and friendly; he was tremendously impressed with the quality of the faculty and students in the Physics Department, and he soon made a wide circle of friends, many, like him, from Europe. As his MSc graduation approached, John was selected for an exchange scholarship to study at Göttingen University in Germany, which was another life-changing experience.

The exchange committed John to return to the University of Saskatchewan to continue his graduate studies. The next three years as he worked towards his PhD were a bit of a grind, but he enjoyed teaching some mathematics courses. His social life revolved around the International Students Club, the Saskatoon German Club and playing soccer. In the two clubs he met a ‘French’ girl — at least he thought she was French because she was speaking French and kept talking about growing up in France — but he soon discovered she was Ukrainian sent by her parents in Montreal to study at a Ukrainian Institute in Saskatoon.

John and Ludmilla were married in Montreal, 8th of May, 1960, nearly 65 years today. After a honeymoon in the UK and continental Europe they set off for Victoria where John had a position at the Pacific Naval Laboratory in Esquimalt.

And so John and Ludmilla left Saskatoon for good in May 1961 and started a new life in Victoria. They bought their first house in Esquimalt; Andrew was born in November 1961; Anthony in February 1965. Many years later their daughter Alexandra was born in 1976.

After five enjoyable and scientifically productive years at PNL, John realised that if he was ever to achieve his goal of eventually returning to his homeland, now was the time to act. One advertised post that seemed particularly attractive was for a mathematics lecturer at a polytechnic in England. The application forms were sent to him, however, by surface rather than air mail, arriving well after the closing date. He returned them anyway and received a very apologetic reply from the head of the department saying he would be notified if other positions became available. Meanwhile, with the University of Victoria expanding rapidly, John received an offer of a permanent position in the Physics Department. He delayed his response as long as possible but eventually, having heard nothing more from the polytechnic, he accepted the faculty position at UVic in 1966. Less than two weeks later, a letter from England did arrive inviting him to apply for one of four positions now available! John often mused how different his journey through life would have been had a wrong stamp not been put on the envelope when mailing the initial application form.

From the time John joined the University of Victoria to his passing, he devoted his research and passion to studying geophysics, in particular geomagnetism. John initially was appointed to the Department of Physics and Astronomy and later cross-appointed with the School of Earth and Ocean Sciences. His breadth of scientific interest, collegiality, and vision for expansion in the Science Faculty all led to his appointment first as Chair of Physics and Astronomy (1980-1988) and then as Dean of Science (1993-1998). As Dean, he not only helped foster growth and development of the new School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, the Centre for Earth and Ocean Research, the VENUS and NEPTUNE cabled ocean observatories, but also more broadly the Centre for Global Studies and instituted a Teaching Awards program. These developments succeeded in part because of his energy, devotion, fairness and openness as an academic administrator.

He remained active well into retirement as a Professor Emeritus and in supporting individuals for scholarships and prizes and mentoring further academic programs within the Faculty of Science. He was entirely unselfish, and became a dependable supporter for new initiatives in research and teaching such as the Canada Research Chairs Program. He was a consummate coach for the Faculty of Sciences and UVic, watching out to help new faculty members and in advancing new initiatives that have helped build UVic’s strong international reputation – elbows up, but always in a gentlemanly posture. Our family has been touched by how fondly John is remembered by his many friends and colleagues from his days at UVic.

John also had a keen interest in local affairs and was a frequent contributor to the Letters section of the Times Colonist. He was an active member of the Rockland Neighbourhood Association and a keen supporter of the Capital Region Municipal Amalgamation Society.

In editing this section of John’s eulogy, we were struck by John’s insistance on pointing out that the “University of Victoria” was an obvious misnomer because one end of the building he worked in was in Oak Bay and the other in Saanich. What a demonstration of John’s keen eye to detail!

In addition to his valuable professional and community contributions, anyone familiar with John would know that many of his greatest contributions were to the lives of his family and friends. John requested his eulogy to be purely factual and chronological, leaving pleasantries aside; however, we believe that pleasantries are not just appropriate, but factual when describing the impact he had on his loved ones. In a break from chronology, we would like to share some warm memories chosen by members of John’s family that highlight the ways he touched the lives of those around him.

His children and grandchildren remember fondly:

- the extraordinary scavenger hunts he would put on for his grandchildren

- His hand-drawn cards (John was a talented artist!)

- Helping every grandchild with math at some point in their life (“Grandpa school”)

- bed-time stories, some short and some unbelievably long and imaginative (Alice and Jane and the penny story)

- trips with his grandchildren, including destinations like Chemainus and a brave tour of England with his French grandchildren

- His culinary specialty – cut along the dotted line soup!

- Teaching his grandchildren to play chess and then later beating them almost every game (the family champion!)

- Buying his grandchildren shirley temples at the faculty club

- Going for walks with his tilly hat and dark sunglasses, even when it was mild and cloudy.

- John falling asleep at the cinema and the kids being embarrassed when he snored

- Endless games of Snakes and Ladders, Loup Garou (although nobody could quite figure out the purpose of this game…), and more.

- Taking his grandchildren to camps in the summer (like sports camps)

- And being loving and accepting of his family no matter what

In his latter years John spent his days visiting Ludmilla at Mt. St. Mary’s. Ludmilla had developed Alzheimers and needed full time care which John could no longer give. John developed a daily ritual, rain or shine, seven days a week of picking Ludmilla up from Mt. St. Mary’s to take her for a drive (or a Trishaw experience). He was always looking for what we lovingly termed “a destination”. Many days involved a walk with Ludmilla around Turkey Head or Clover Point (John would always point out how the picnic tables were never used!). Other days he would stop at Alexandra’s or their house in Rockland for tea. And sometimes it simply involved a soft ice cream cone at the Beacon Drive in. The staff at Mt. St. Mary’s frequently commented on John’s incredible dedication to his wife.

John lived a very full life and always took a genuine interest in the lives of others. In the later years of his life, in addition to all that was mentioned above, he spent his time:

- Attending Friday evenings at the Faculty Club with the “regular crew”.

- Spending time with family, his three children and many grandchildren (including treating them to their annual trip to the Deep Cove Chalet)

- Enjoying walks with the Cathedral Walking Group

- Hosting (expert level!) trivia for his neighbours at Amica Somerset even through his health struggles.

- Enjoying the finer treats in life, like nespressos, marmalade, and gin martinis!

- Researching his genealogical roots and putting together the family history with the help of his daughter-in-law, Laurence, for the benefit of his grandchildren

- And writing articles on a vast array of subjects, from mathematics to public policy, on his personal blog Beorminga.

Not long before his passing, John remarked on how much he loved his family and how proud he was of his children, Andrew, Anthony and Alexandra. On his last day, he was surrounded by family. All of his children and grandchildren were there with him in the room or connected via video call (from all around the world no less). He passed peacefully, holding my (Maria) and my father’s hands. John is loved and dearly missed.

A close family friend visited John during his final hours and shared some words on the end of life from her late husband. We’d like to end off by sharing an extract from a funeral address by the late Desmond Carroll that we think John would have appreciated.

“The end of life brings us to a threshold as we face that mysterious place where the known and the unknown intersect. We ponder, with all those emotions that seek to understand, what may be beyond. As we were sustained and comforted in our lives by love, there is a greater love that waits on the other side of the threshold that understands our humanity…

Electing Strong Island Voices for a Strong Canada

Sunday, March 9, 2025, Dürres, Albania:

Mark Carney was just elected to lead the Liberals into the forthcoming Canadian federal election. This election is turning out to be one of the most important in Canadian history.

In Russia, Valdimir Putin continues his expansionist dreams of rebuilding the Soviet Union through his latest campaign of terror, violence and war crimes now aimed at the Ukrainian people. Meanwhile, in the middle east, Gaza lays in ruins, the Syrian government has been overthrown, and tensions continue between the Israeli government and the Iran-supported terror organizations Hamas, Hizballah, and the Houthis. In Europe, Germany’s far right Alternative for Germany (AfG) party made stunning gains in the 2025 election. Virtually every region of the country that was once under East German communist rule supported the anti-immigration AfD campaign. Meanwhile many parts of Africa and Asia continue to experience civil unrest.

Historically, the world would have turned to America and its NATO allies to broker peace and maintain world order. But all that has changed with the election of Donald Trump. He is waging trade wars against allied nations thereby undermining international trade and security agreements. He insults international leaders on an almost daily basis. Whether it be calling Prime Minister Justin Trudeau the Governor of the great state of Canada or acting like a school yard bully to publicly demean Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy, the man has no limit.

The chaos created by Donald Trump has caused the Dow Jones Industrial Average to tumble recently, completing a classic double-top trading pattern suggesting a major market correction is in the cards. His delusional dreams of rebuilding Gaza into a Mediterranean paradise, or annexing Greenland and Canada are all signs of a very disturbed man. Donald Trump is making America weak again.

Donald Trump’s niece Mary Trump holds a PhD in clinical psychology from Adelphi University’s Derner Institute of Advanced Psychological Studies, the first university-based professional school of psychology in America. As a clinical psychologist and daughter of Donald Trump’s older brother Fred, she is uniquely qualified to comment on the president’s psychiatric condition. She didn’t hold back in her tell-all book Too Much and Never Enough: How My Family Created The World’s Most Dangerous Man.

Donald Trump’s niece Mary Trump holds a PhD in clinical psychology from Adelphi University’s Derner Institute of Advanced Psychological Studies, the first university-based professional school of psychology in America. As a clinical psychologist and daughter of Donald Trump’s older brother Fred, she is uniquely qualified to comment on the president’s psychiatric condition. She didn’t hold back in her tell-all book Too Much and Never Enough: How My Family Created The World’s Most Dangerous Man.

There she writes that he displays all nine characteristics of narcissistic personality disorder as detailed in the American Psychiatric Society’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. She further suggests that he may suffer from dependent personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder and “long undiagnosed learning disability that for decades has interfered with his ability to process information.” Perhaps this explains his behaviour, admiration of authoritarian demagogues and chaotic approach to governance.

But at the same time, it’s easy to manipulate such an individual by simply playing to their unabated, all-consuming egotism. And so, Trump has surrounded himself with sycophants, the brightest of whom know how to influence him to get exactly what they want.

For much of the spring term, I’ve been on sabbatical in Albania. It’s been a life changing experience as I’ve got to know the people and the country. Albania is a new democracy and much of the country has been rebuilt this century. Memories of persecution and terror under the communist dictatorship that ended in 1991 as well as the 1997 civil war are still fresh in people’s minds. Life is hard for many.

Albania still has a few governance and infrastructure wrinkles to iron out prior its planned 2030 entry into the European Union. But the spring in the gait of the hardworking people, the joyous interactions I had with so many, and the generosity of those who had so little to give affected me deeply. It’s a society where people look out for one another.

Albania still has a few governance and infrastructure wrinkles to iron out prior its planned 2030 entry into the European Union. But the spring in the gait of the hardworking people, the joyous interactions I had with so many, and the generosity of those who had so little to give affected me deeply. It’s a society where people look out for one another.

While officially a secular state, more than half of Albanians are Muslim. The Muslim majority live in harmony with the Orthodox and Catholic minorities. Like France, Albania only recognizes civil unions and so its not uncommon to see muslims marry christians or orthodox wed catholics.

Yet while Albanians celebrate their freedom and newly found democracy, America is heading in the opposite direction. Even here in British Columbia, the BC NDP’s introduction of Bill 7 — Economic Stabilization (Tariff Response) Act signalled a disturbing trend towards more autocratic governance. Vancouver columnist Vaughn Palmer writes “In 41 years of covering B.C. governments, I’ve not seen a legislation as arbitrary and far-reaching this side of the federal War Measures Act.”

Since the inauguration of Trump, Canadian sovereignty has come under attack. Watching this from afar was very difficult. It’s critical that Canada has stabled principled leadership in these difficult times. And Mark Carney is exactly the type of person Canada needs. The Conservative Party appears to have been taken over by extreme elements whose behaviour mirrors that of the Republican Party south of the border. Those identifying with the progressive conservative roots of the Conservative Party have been left feeling alienated; the NDP do not have the leadership required to take on Donald Trump, and the Canadian Greens are disorganized and mired with never-ending infighting.

But here’s the dilemma. On Vancouver Island we are not voting for Carney. We are voting for the Member of Parliament that we believe will best represent us in Ottawa. In my view, the Liberals have yet again overlooked the island thereby stoking our underlying sense of western alienation. None of their south island candidates inspire me to want to vote for them as I do not believe they will be strong advocates for our region. The Liberal south island candidates recently moved here from somewhere else in Canada. Two of their rookie candidates are already mired in scandal. In the case of Will Greaves, an unfortunate twitter post from March 2024 led Rabbi Meir Kaplan to write to Prime Minister Carney asking him to reconsider Mr. Greaves’ candidacy for his “public statements that echo classic antisemitic tropes”.

But here’s the dilemma. On Vancouver Island we are not voting for Carney. We are voting for the Member of Parliament that we believe will best represent us in Ottawa. In my view, the Liberals have yet again overlooked the island thereby stoking our underlying sense of western alienation. None of their south island candidates inspire me to want to vote for them as I do not believe they will be strong advocates for our region. The Liberal south island candidates recently moved here from somewhere else in Canada. Two of their rookie candidates are already mired in scandal. In the case of Will Greaves, an unfortunate twitter post from March 2024 led Rabbi Meir Kaplan to write to Prime Minister Carney asking him to reconsider Mr. Greaves’ candidacy for his “public statements that echo classic antisemitic tropes”.

Esquimalt-Saanich-Sooke Liberal candidate Stephanie McLean, on the other hand, who resigned from the Alberta legislature before completing her first term, has been called out by her own NDP colleagues for her musings about the ability of MLAs to advocate inside government caucus. I was surprised that the Liberals would think that a controversial former NDP MLA from Alberta would make a good candidate to run against Maja Tait, the present Mayor of Sooke, who I approached to run with the BC Greens in the 2017 provincial election. Maja has deep roots in the community and has has an exemplary record of public service in Sooke.

Friday, April 18, 2025, Victoria, British Columbia:

Today I waited in line for over two hours to cast my vote for Elizabeth May in the riding of Saanich Gulf Islands. While it would have been easy for me to vote for Saanich Councillor and NDP candidate Colin Plant, who I have known for quite some time and who I believe exemplifies stellar leadership in governance, I was concerned that without Elizabeth in Ottawa, critical environmental issues will be swept under the rug during parliamentary debates.

Today I waited in line for over two hours to cast my vote for Elizabeth May in the riding of Saanich Gulf Islands. While it would have been easy for me to vote for Saanich Councillor and NDP candidate Colin Plant, who I have known for quite some time and who I believe exemplifies stellar leadership in governance, I was concerned that without Elizabeth in Ottawa, critical environmental issues will be swept under the rug during parliamentary debates.

Like many of you, I have heard the NDP ads on the radio or seen the signs stating that we vote NDP to stop the conservatives on Vancouver Island. I agree in principle, with two notable exceptions. The candidates I list below I have either worked with or know quite well. Were I to reside in their ridings, I would vote for them knowing that they would advocate for Vancouver Island interests in Ottawa.

And finally, I am a huge fan of minority governments and I do not trust the Federal Liberals to be given free range with a majority government. While I desperately want Mark Carney to be our Prime Minister, I think it would be prudent for Canadians to ensure that NDP, Green and perhaps Bloc incumbents are elected to keep them honest. The leader of the Federal Liberals may have changed, but I remain unconvinced that the party insiders and staffers have taken heed of the message that they were sent by Canadians.

Let’s not split the vote on Vancouver Island and instead consider supporting the following candidates to ensure Mark Carney and the Federal Liberals have a minority government where our voices are heard!

These are the candidates I believe will best represent us on Vancouver Island:

1) Laurel Collins – NDP – Victoria

2) Gord Johns – NDP – Courtenay-Alberni

3) Alistair MacGregor – NDP -Cowichan-Malahat-Sooke

4) Paul Manly Green – Nanaimo-Ladysmith

5) Elizabeth May – Green – Saanich- Gulf Islands

6) Maja Tait – NDP – Esquimalt-Sooke-Saanich

The Paris Agreement is in trouble: UNFCCC needs to ratchet up their climate efforts

Earlier this week I had an article published in The Conversation. As Facebook appears to be blocking reposting of Canadian news articles, I have reproduced a version of it below. This version includes more information and a video produced by, and reproduced with the permission of Myles Allen.

Expanded Version of The Conversation article

Negotiations at the 29th Conference of Parties (COP29) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) are entering their second week after things got off to a rocky start.

Even before the event started, many were stunned that COP29 would again be hosted by a petro state. Just last year, COP28 was held in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, and this year it is Azerbaijan’s turn. Approximately 90 per cent of Azerbaijan’s exports are in the oil and gas sector.

The president of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev, has described oil and gas resources as a “gift of god.” Meanwhile, the country’s deputy energy minister (and chief executive of COP29) has been caught on tape using the conference to advance oil investment deals.

What is the UNFCCC

The UNFCCC was established in 1992 and open for signature at the famous Earth Summit at United Nations Conference on Environment and Development held in Rio de Janeiro from June 3 to 14, 1992, where Canada signed. In total, 198 countries are now parties to the UNFCCC, which formally came into force March 21, 1994. Its main objective is:

“stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system.”

To address this objective, parties to the UNFCCC adopted a legally binding international treaty, known at the Paris Agreement, at COP21 in Paris. The overarching goal of the Paris Agreement is:

“Holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change”.

How successful have international negotiations been?

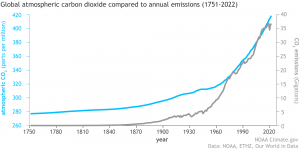

Since the establishment of the UNFCCC, the globally-averaged atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration has increased 18% (from 356 to 421 ppm) and the globally-averaged methane concentration has increased 11% (from 1735 to 1922 ppb). During this time the 5-year average rate of carbon dioxide increase has almost doubled from 1.3 ppm/years in 1992 to 2.5 ppm/year in 2023.

Over the period 1992-2023 the global mean temperature has risen 0.9°C, now sitting at 1.18°C above the 20th century average and rising at 0.23 °C/decade. And when all anthropogenic greenhouse gases are converted to their carbon dioxide equivalent, the atmospheric concentration is 534 ppm CO2e approaching twice the preindustrial value.

Over the period 1992-2023 the global mean temperature has risen 0.9°C, now sitting at 1.18°C above the 20th century average and rising at 0.23 °C/decade. And when all anthropogenic greenhouse gases are converted to their carbon dioxide equivalent, the atmospheric concentration is 534 ppm CO2e approaching twice the preindustrial value.

At the same time, and despite more than three decades of negotiations, 2023 was 1.48°C warmer than the 1850-1900 preindustrial average and its looking like 2024 will be even warmer, almost certainly surpassing the 1.5°C mark for the first time.

International negotiations have clearly failed to decrease anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions or stabilize global mean temperatures.

International negotiations have clearly failed to decrease anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions or stabilize global mean temperatures.

Neverthelss. the UAE Consensus, a landmark achievement of last year’s COP28, committed the parties to “transitioning away from all fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner in this critical decade to enable the world to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, in keeping with the science.”

This, however, begs an important question. Just what exactly does it mean to reach net-zero emissions “in keeping with the science?” I was a co-author in a recently published landmark study that may just help provide the answer.

What is net zero?

Defining net zero requires an understanding of timescales. Millions of years ago, trees, ferns and other plants were abundant when the atmosphere had much higher concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2).

As the years went by, plants would grow and die. This dead vegetation would fall into swampy waters and, in time, turn into peat. Over millions of years, the peat turned into brown coal, then soft coal, and finally hard coal.

As the years went by, plants would grow and die. This dead vegetation would fall into swampy waters and, in time, turn into peat. Over millions of years, the peat turned into brown coal, then soft coal, and finally hard coal.

A similar process occurred within shallow seas where ocean plants (such as phytoplankton) and marine creatures would die and sink to the bottom to be buried in the sediments below.

Over millions of years, the sediments hardened to produce sedimentary rocks, and the resulting high pressures and temperatures caused the organic matter to transform slowly into oil or natural gas. The great oil and natural gas reserves of today formed in these ancient sedimentary basins.

Today, when we burn a fossil fuel, we are harvesting the sun’s energy stored in a life that lived millions of years ago. In burning fossil fuels, we release the carbon dioxide that had been drawn out of that ancient atmosphere — the same ancient atmosphere that had much higher levels of carbon dioxide than today.

Simply put, unless we can figure out a way to speed up the millions of years of geologic process, the idea that we can stop global warming solely through nature-based solutions or “planting a tree” simply isn’t realistic.

Reaching true net zero?

A series of scientific analyses published in 2007, February 2008, August 2008 and 2009 demonstrated that the stabilization of global mean temperatures required net-zero emissions. Policymakers interpreted these findings as a green light to emit carbon as long as these were natural “offsets.” This is a gross misinterpretation of the facts of net zero.

And so I, alongside a global team of 25 scholars and scientists involved in the early research, teamed up to correct this misinterpretation and explain just what exactly is (and is not) net zero.

Our research, recently published in Nature, makes four key recommendations for reaching true net zero:

- Stabilization of the global mean temperature at any level requires net-zero anthropogenic emissions;

- Reliance on “natural carbon sinks” like forests and oceans to offset ongoing carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from fossil fuel use will not actually stop global warming;

- “Net zero” must be interpreted as “geological net zero” wherein each ton of carbon dioxide emissions released to the atmosphere through fossil fuel combustion is balanced by a ton of atmospheric carbon dioxide sequestered in geological storage;

- Governments and corporations are increasingly seeking carbon offset credit for the preservation of natural carbon sinks. Protection of natural sinks cannot be used to offset ongoing fossil fuel emissions if net zero is to halt warming;

Human activities since 1750 have emitted 2,634 billion tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere; 1,814 billion tons (69 per cent) of our total emissions originated from the combustion of fossil fuels and 820 billion tons (31 per cent) from changes in land use such as deforestation. As such, nature-based solutions only have a limited role to play in emissions reduction and certainly can’t be used to offset future emissions from fossil fuel combustion.

Nature-based solutions do, however, have an important role to play in climate change adaptation and the preservation of biodiversity, but there is a growing danger that governments, industry and the public will come to rely on them to maintain the status quo. This impulse must be avoided at all costs.

The example of British Columbia